|

|

|

And yet despite the look on my face, you’re still talking and thinking that I care, Anonymous

The complex plane $\mathbb{C}$ is unbounded, so points can “go or blow off to infinity” in many directions. To study the behavior of functions “at infinity” and to give $\infty$ equal footing with finite complex numbers, we adjoin one extra point and obtain the extended complex plane $\mathbb{C}^* = \mathbb{C} \cup \{ \infty \}$

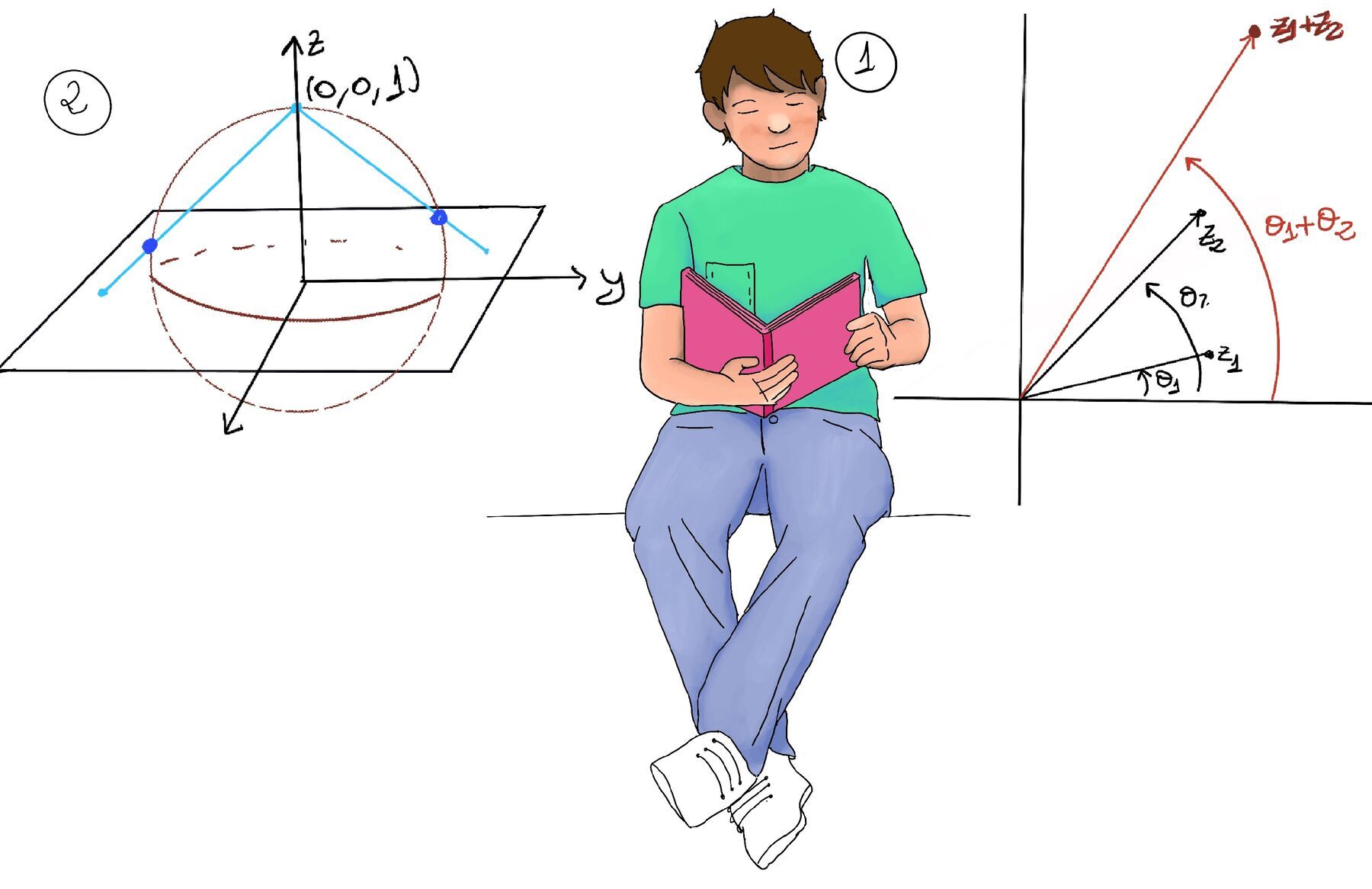

The stereographic projection maps a complex point z = x + iy, regarded as the point (x, y, 0) to the unique point Z = (x₁, y₁, z₁) on the sphere (other than $N$) that lies on the line through N and z (Figure 2). That ray strikes S at exactly one other point Z = (x1, y1, z1). The map $\pi: \mathbb{C} \to S \setminus \{N\}, (x, y, 0) \to (x₁, y₁, z₁)$ is the stereographic projection. In this way each point on the complex plane corresponds uniquely to a point on the surface of the sphere.

The ray from $N$ through $z$. The line connecting N(0, 0, 1) and z(x, y, 0) can be parameterized as: $\mathbf{L}(t) = tN + (1-t)z = t(0, 0, 1) + (1-t)(x, y, 0) = ((1-t)x, (1-t)y, t), \quad t \in \mathbb{R}$

To find the intersection with the sphere. To find the intersection point, we substitute the coordinates of $\mathbf{L}(t)$ into the equation of the sphere, and we get:

$$ \begin{aligned} (1-t)^2 x^2 + (1-t)^2 y^2 + t^2 = 1 &\implies (1-t)^2(x^2 + y^2) + t^2 = 1 \\[2pt] &\implies (1-t)^2|z|^2 + t^2 = 1\\[2pt] &\implies[\text{Expanding and rearrange to a quadratic in t}] |z|^2(1 - 2t + t^2) + t^2 = 1 \\[2pt] &\implies |z|^2 - 2|z|^2 t + |z|^2 t^2 + t^2 = 1 \\[2pt] &\implies t^2(|z|^2 + 1) - 2|z|^2 t + (|z|^2 - 1) = 0 \\[2pt] &\implies[\text{Solving the quadratic equation}] t = \frac{2|z|^2 \pm \sqrt{4|z|^4 - 4(|z|^2 + 1)(|z|^2 - 1)}}{2(|z|^2 + 1)} \\[2pt] &\implies[\text{Simplifying the discriminant:}] 4|z|^4 - 4(|z|^4 - 1) = 4|z|^4 - 4|z|^4 + 4 = 4 \\[2pt] &\implies t = \frac{2|z|^2 \pm 2}{2(|z|^2 + 1)} = \frac{|z|^2 \pm 1}{|z|^2 + 1} \\[2pt] \end{aligned} $$We have two solutions for t:

Forward projection: $\pi: \mathbb{C} \to S \setminus \{N\}$

Using $t = \frac{|z|^2 - 1}{|z|^2 + 1}$ and $1 - t = \frac{2}{|z|^2 + 1}$, we obtain the projection: $\boxed{\pi(z) = (x_1, y_1, z_1) = \left(\frac{2x}{|z|^2 + 1}, \frac{2y}{|z|^2 + 1}, \frac{|z|^2 - 1}{|z|^2 + 1}\right)}$ (coordinates on the sphere).

In terms of $z$ and $\bar{z}$. Since $x = \frac{z + \bar{z}}{2}$ and $y = \frac{z - \bar{z}}{2i}$, $\pi(z) = \left(\frac{z + \bar{z}}{|z|^2 + 1}, \frac{z - \bar{z}}{i(|z|^2 + 1)}, \frac{|z|^2 - 1}{|z|^2 + 1}\right)$

Inverse projection: $\pi^{-1}: S \setminus \{N\} \to \mathbb{C}$

Given a point $(x_1, y_1, z_1)$ on the sphere S with $z_1 \neq 1$ (other than the north pole with z₁ ≠ 1), we can find the corresponding complex number z in the plane: $\boxed{z = \pi^{-1}(x_1, y_1, z_1) = \frac{x_1 + iy_1}{1 - z_1}}$

Verification: $\frac{x_1 + iy_1}{1 - z_1} = \frac{\frac{z + \bar{z}}{|z|^2 + 1} + i \cdot \frac{z - \bar{z}}{i(|z|^2 + 1)}}{1 - \frac{|z|^2 - 1}{|z|^2 + 1}} = \frac{\frac{z + \bar{z} + z - \bar{z}}{|z|^2 + 1}}{\frac{|z|^2 + 1 - |z|^2 + 1}{|z|^2 + 1}} = \frac{\frac{2z}{|z|^2 + 1}}{\frac{2}{|z|^2 + 1}} = z \quad \checkmark$. This check shows the formula is exactly the inverse of the forward stereographic projection.

The stereographic projection establishes a one-to-one correspondence between the complex plane ℂ and the unit sphere S excluding the north pole N. To complete the correspondence, we add a point at infinity (∞) to ℂ and map it to the north pole N. This extended complex plane ℂ ∪ {∞} is called the Riemann sphere.

In the extended complex plane (the Riemann sphere), we declare π−1(N) = ∞. The resulting bijection ℂ ∪ {∞} ≅ S is the Riemann sphere. Formally, $\hat{\mathbb{C}} = \mathbb{C} \cup \{\infty\}$, where we define $\pi(\infty) = N = (0, 0, 1)$.

Key Properties of Stereographic Projection:

In the extended complex plane (Riemann sphere) $\hat{\mathbb{C}} = \mathbb{C} \cup \{\infty\}$, arithmetic operations involving ∞ are defined to preserve geometric and analytic consistency.

For $a \in \mathbb{C}$:

| Operation | Result | Condition |

|---|---|---|

| $a + \infty$ | $\infty$ | Adding any finite value to ∞ remains ∞, reflecting the unbounded nature of infinity |

| $a \cdot \infty$ | $\infty$ | $a \neq 0$, scaling ∞ by a non-zero finite value preserves infinity |

| $\frac{a}{\infty}$ | $0$ | Dividing a finite value by infinity approaches zero, consistent with limits |

| $\frac{a}{0}$ | $\infty$ | $a \neq 0$ Division by zero maps to infinity, corresponding to poles in meromorphic functions, e.g., 1/z |

| $\infty + \infty$ | Undefined | Indeterminate form as it lacks a unique interpretation |

| $0 \cdot \infty$ | Undefined | Indeterminate form as it lacks a unique interpretation |

| $\frac{0}{0}$ | Undefined | Indeterminate form |

| $\frac{\infty}{\infty}$ | Undefined | Indeterminate form |

The chordal metric (or spherical metric) provides a way to measure distances between points on the extended complex plane $\hat{\mathbb{C}}$ by treating them as points on a physical sphere.

The chordal distance d(z, w) between two points on the Riemann sphere is the straight-line Euclidean distance in $\mathbb{R}^3$ between their projections on the sphere S.

For any complex number $z = x + iy$, its projection $\pi(z) = (x_1, x_2, x_3)$ onto the sphere is given by: $x_1 = \frac{2x}{1+|z|^2}, x_2 = \frac{2y}{1+|z|^2}, x_3 = \frac{|z|^2-1}{|z|^2+1}$. The point at infinity $\infty$ is mapped directly to the North Pole $N(0, 0, 1)$.

For any $z, w \in \hat{\mathbb{C}}$:

$d(z, w) = \begin{cases} \|\pi(z) - \pi(w)\|_{\mathbb{R}^3}, &z, w \ne \infty\\\\ \frac{2}{\sqrt{1+|z|²}}, &w = \infty \end{cases}$

$d(z, w) = \begin{cases} \frac{2|z - w|}{\sqrt{(1 + |z|^2)(1 + |w|^2)}} & z, w \neq \infty \\ \frac{2}{\sqrt{1+|z|^2}} & w = \infty \end{cases}$

Let’s derive why $d(z, \infty) = \frac{2}{\sqrt{1+|z|^2}}$. We calculate the distance between $\pi(z) = (x_1, x_2, x_3)$ and the North Pole $N = (0, 0, 1)$ (the point at infinity ∞ is mapped directly to the north pole N = (0, 0, 1) of the unit sphere S), $d(z, \infty)^2 = (x_1 - 0)^2 + (x_2 - 0)^2 + (x_3 - 1)^2$

Since $x_1^2 + x_2^2 = \frac{(2x)^2 + (2y)^2}{(1+|z|^2)^2} = \frac{4(x^2+y^2)}{(1+|z|^2)^2}$, and $x^2 + y^2 = |z|^2$: $x_1^2 + x_2^2 = \frac{4|z|^2}{(1+|z|^2)^2}$

$x_3 - 1 = \frac{|z|^2 - 1}{|z|^2 + 1} - 1 = \frac{|z|^2 - 1 - (|z|^2 + 1)}{|z|^2 + 1} = \frac{-2}{|z|^2 + 1}$

Therefore, $d(z, ∞)^2 = (x_1-0)^2+(y_1-0)^2+(z_1-1)^2 = \frac{4|z|^2}{(1+|z|^2)^2} + \frac{4}{(1+|z|^2)^2} = \frac{4·(1+|z|^2)}{(1+|z|^2)^2} = \frac{4}{1+|z|^2}$

Taking the square root gives the previous formula: $d(Z, ∞) = \frac{2}{\sqrt{1+|z|²}}$

This correspondence along with the distance is called the stereographic projection.

Key properties of the Chordal Metric:

The Riemann sphere is a compact space (closed and bounded in $\mathbb{R}^3$), so all distances are finite. The maximum distance between any two points on the unit sphere is the diameter, which is 2 (the distance between the north pole N = (0, 0, 1) and south pole S = (0, 0, −1)). For any $z, w \in \hat{\mathbb{C}} $, the chordal distance d(z, w) is the Euclidean distance in $\mathbb{R}^3$ between their projections π(z) and π(w) on the sphere. Since the sphere has radius 1, the maximum Euclidean distance between two points is 2.

The origin z = 0 maps to the south pole S = (0, 0, −1), and ∞ maps to the north pole N = (0, 0, 1). The Euclidean distance between S and N in $\mathbb{R}^3$ is 2, which is the diameter of the sphere.