|

|

|

When the world says, ‘Give up,’ hope whispers, ‘Try it one more time’, Lyndon B. Johnson

The equation |z - a| = r defines a circle in the complex plane where the distance between any point z on the circle and the center a is equal to the radius r. Components:

The absolute value |z - a| represents the Euclidean distance between points z and a in the complex plane. This distance formula is: |z - a| = |x + yi - (h + ki)| = |(x - h) + (y - k)i| = $\sqrt{(x - h)² + (y - k)²}$

Setting this equal to $r$: $\sqrt{(x - h)^2 + (y - k)^2} = r$. Then, squaring both sides, we get the familiar Cartesian equation of a circle! $\boxed{(x - h)^2 + (y - k)^2 = r^2}$

| Inequality | Region | Description |

|---|---|---|

| $\vert z - a\vert < r$ | Open disk | Interior of circle (excluding boundary) |

| $\vert z - a\vert \leq r$ | Closed disk | Interior plus boundary |

| $\vert z - a\vert > r$ | Exterior | Outside the circle |

| $\vert z - a\vert \geq r$ | Closed exterior | Outside plus boundary |

| $\vert z - a\vert = r$ | Circle | Boundary only |

| Notation | Region |

|---|---|

| $r_1 < \vert z - a\vert < r_2$ where $0 < r_1 < r_2$ | Open annulus (ring-shaped region) centered at a |

| $r_1 ≤ \vert z - a\vert ≤ r_2$ | Closed annulus |

| $r_1 < \vert z - a\vert≤ r_2$ | Half-open annulus |

| $0 < \vert z - a\vert < r$ | Punctured disk (center removed) |

| $\vert z - a\vert > r$ | Exterior of disk |

Lines in the complex plane can be written as: $\Re(\bar{a}z) = c \quad \text{or} \quad \Im(\bar{a}z) = c$ with $a \in \mathbb{C} \setminus \{ 0 \}$ and $c \in \mathbb{R}$

Write a = u + iv (where u, v are real numbers) and z = x + iy (where x, y are real coordinates). Then, $\overline{a}z = (u -iv)(x +iy)=(ux +vy) +i(uy -vx)$.

In analytic geometry, a line in a 2D plane is defined by the equation: Ax + By = C where (A, B) is the normal vector (a vector perpendicular to the line).

If you have a vector (u, v), rotating it 90∘ counter-clockwise swaps the components and negates the first one.

Half-planes

| Inequality | Region |

|---|---|

| $\Re(z) > 0$ | Right half-plane |

| $\Re(z) < 0$ | Left half-plane |

| $\Im(z) > 0$ | Upper half-plane |

| $\Im(z) < 0$ | Lower half-plane |

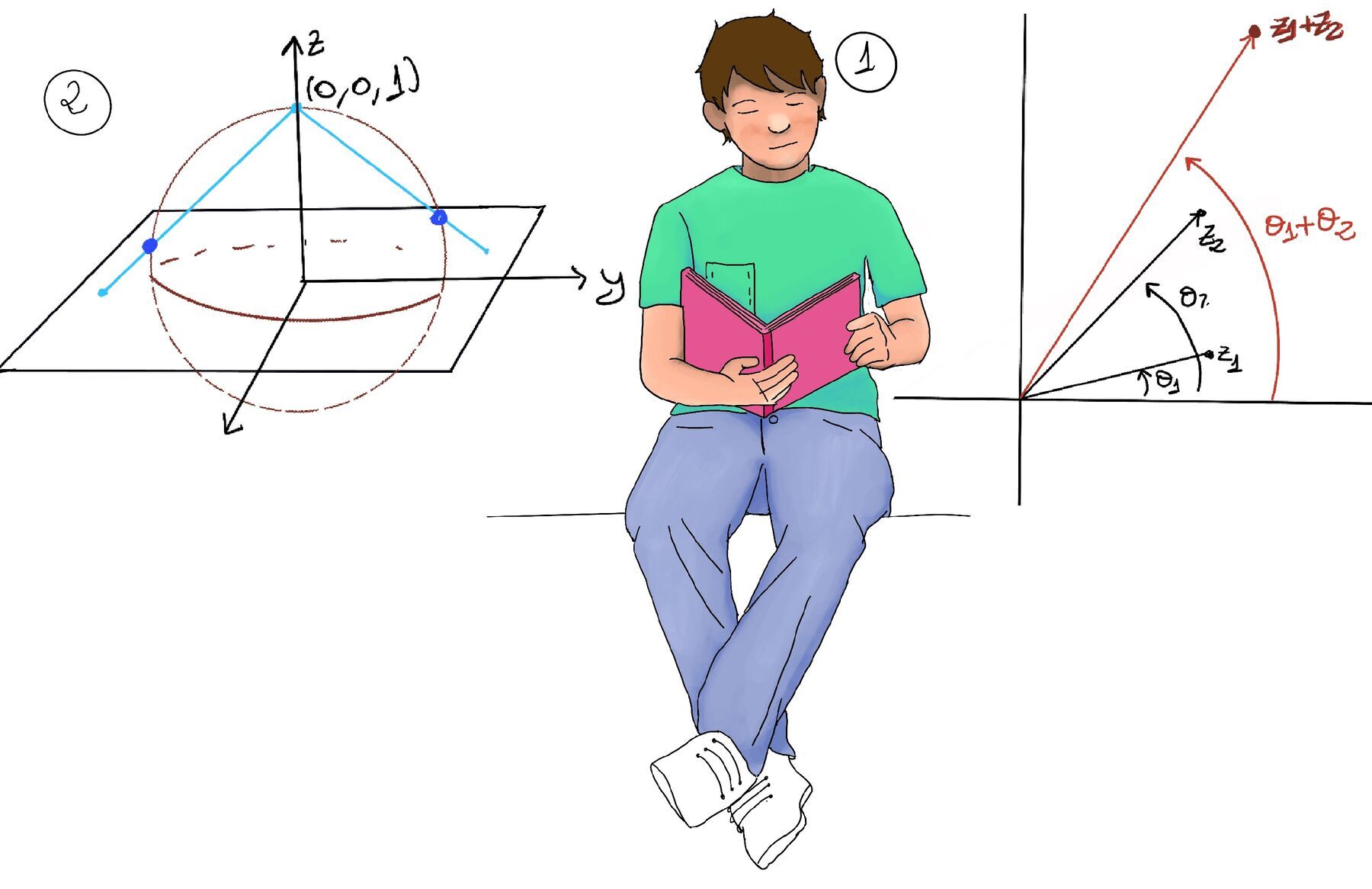

Let two complex numbers be given in polar form: $z_1 = r_1(cos(\theta_1) + isin(\theta_1)), z_2 = r_2(cos(\theta_2) + isin(\theta_2))$.

Derivation of Product Formula.

$$ \begin{aligned} z_1 \cdot z_2 &=r_1(\cos\theta_1 + i\sin\theta_1) \cdot r_2(\cos\theta_2 + i\sin\theta_2) \\[2pt] &= r_1 r_2 [(\cos\theta_1 + i\sin\theta_1)(\cos\theta_2 + i\sin\theta_2)] \\[2pt] &=[\text{Expanding}]r_1 r_2 [\cos\theta_1\cos\theta_2 + i\cos\theta_1\sin\theta_2 + i\sin\theta_1\cos\theta_2 + i^2\sin\theta_1\sin\theta_2] \\[2pt] &= r_1 r_2 [(\cos\theta_1\cos\theta_2 - \sin\theta_1\sin\theta_2) + i(\sin\theta_1\cos\theta_2 + \cos\theta_1\sin\theta_2)] \\[2pt] &\text{Using the angle addition formulas:} \cos(\alpha + \beta) = \cos\alpha\cos\beta - \sin\alpha\sin\beta, \sin(\alpha + \beta) = \sin\alpha\cos\beta + \cos\alpha\sin\beta \\[2pt] &= r_1 r_2 [\cos(\theta_1 + \theta_2) + i\sin(\theta_1 + \theta_2)] \end{aligned} $$$\boxed{z_1 \cdot z_2 = r_1 r_2 [\cos(\theta_1 + \theta_2) + i\sin(\theta_1 + \theta_2)]}$

The Multiplication Rules:

$\frac{z_1}{z_2} = \frac{r_1 e^{i\theta_1}}{r_2 e^{i\theta_2}} = \frac{r_1}{r_2} e^{i(\theta_1 - \theta_2)}$

The Division Rules:

De Moivre’s Theorem: For any complex number $z = r(\cos\theta + i\sin\theta)$ and any $n$: $\boxed{z^n = r^n(\cos(n\theta) + i\sin(n\theta))}, \boxed{(\cos\theta + i\sin\theta)^n = \cos(n\theta) + i\sin(n\theta)}$. Or in exponential notation: $\boxed{(e^{i\theta})^n = e^{in\theta}}$

Proof by Induction

Base Cases: It is obviously a true statement for n = 0 ($z^0 = 1 = r^0(cos(0) + isin(0))$) and 1 ($z^1 = r(\cos\theta + i\sin\theta) = r^1(\cos(1 \cdot \theta) + i\sin(1 \cdot \theta)) \quad \checkmark$).

Inductive step: Assume the theorem holds for n = k, $z^k = r^k(\cos(k\theta) + i\sin(k\theta))$. We aim to prove it for n = k + 1.

$$ \begin{aligned} z^{k+1} &=z^k \cdot z \\[2pt] &\text{Inductive step, n = k} \\[2pt] &=r^k(\cos(k\theta) + i\sin(k\theta)) \cdot r(\cos\theta + i\sin\theta) \\[2pt] &=r^{k+1}[(\cos(k\theta)\cos\theta - \sin(k\theta)\sin\theta) + i(\cos(k\theta)\sin\theta + \sin(k\theta)\cos\theta)]\\[2pt] &\text{Using angle addition formulas: sin(α + β) = sin α cos β + cos α sin β and cos(α + β) = cos α cos β - sin α sin β} \\[2pt] &= r^{k+1}[\cos((k+1)\theta) + i\sin((k+1)\theta)] \quad \blacksquare \end{aligned} $$Extension to Negative Integer. For n = -1:

$$ \begin{aligned} z^{-1} = \frac{1}{z} &=\frac{1}{r(\cos\theta + i\sin\theta)}\\[2pt] &\text{[Multiply by conjugate:]} =\frac{1}{r} \cdot \frac{\cos\theta - i\sin\theta}{(\cos\theta + i\sin\theta)(\cos\theta - i\sin\theta)} \\[2pt] &= \frac{1}{r} \cdot \frac{\cos\theta - i\sin\theta}{\cos^2\theta + \sin^2\theta} \\[2pt] &= \frac{1}{r}(\cos\theta - i\sin\theta) = r^{-1}(\cos(-\theta) + i\sin(-\theta)) \quad \checkmark \end{aligned} $$For general negative $n = -m$ (where $m > 0$):

$$ \begin{aligned} z^{-m} &=(z^m)^{-1} \\[2pt] &[\text{By previous demonstration, the equality holds }] \\[2pt] &=\frac{1}{r^m(\cos(m\theta) + i\sin(m\theta))} \\[2pt] &=\frac{1}{r^m(\cos(m\theta) + i\sin(m\theta))}\frac{\cos(m\theta) - i\sin(m\theta)}{\cos(m\theta) - i\sin(m\theta)} = r^{-m}(\frac{\cos(m\theta) - i\sin(m\theta)}{\cos^2(m\theta) + \sin^2(m\theta)}) \\[2pt] &= r^{-m}(\cos(-m\theta) + i\sin(-m\theta)) \quad \checkmark \end{aligned} $$De Moivre's Theorem. $z^n = r^n(cos(n\theta)+isin(n\theta))$ and the equality holds $\forall n \in \mathbb{Z}.$

Alternative Proof Using Euler’s Formula: $(\cos\theta + i\sin\theta)^n =[\text{Euler's formula}] (e^{i\theta})^n =[\text{Exponential law: } (e^a)^n = e^{an}] e^{in\theta} = \cos(n\theta) + i\sin(n\theta) \quad \blacksquare$

Given $z = re^{i\theta}$, find all $w$ such that $w^n = z$. General Solution: $\boxed{w_k = r^{1/n} e^{i(\theta + 2\pi k)/n} = \sqrt[n]{r}\left(\cos\frac{\theta + 2\pi k}{n} + i\sin\frac{\theta + 2\pi k}{n}\right)}$ for $k = 0, 1, 2, \ldots, n-1$

There are exactly $n$ distinct roots, one for each k = 0, 1, …, n-1. All roots have the same modulus $\vert w_k\vert \ = \sqrt[n]{r} = \vert z \vert^{1/n}$. Consecutive roots’ arguments differ by $\frac{2\pi}{n}$ radians, so they lie on a circle of radius $\sqrt[n]{r}$ centered at the origin and form the vertices of a regular n-gon. If $\theta = Arg(z)$, then the principal n-th root is $w_0 = \sqrt[n]{r} e^{i\theta/n}$ (when $\theta = \text{Arg}(z)$) and the other roots are obtained by successively adding $\frac{2\pi}{n}$ to its argument.

If $z \ne 0$ and we write it in polar form as $z = |z| e^{iArg(z)}$, then all the $n$-th roots of $z$ can be written as: $\boxed{w_k = \sqrt[n]{z} \cdot \omega_n^k}$, k = 0, 1, …, n- 1 where: