|

|

|

“Mr. Smith, could you explain to us what recursion is all about?” The professor in Introduction to Programming asked an apathetic student. “I don’t know the question, but sex, money, or both is definitely the answer, and God, justice, our values, and love are just the excuses,” I replied. “You shall not pass,” the teacher was far from amused, Apocalypse, Anawim, #justtothepoint.

Definition. A function f is a rule, relationship, or correspondence that assigns to each element x in a set D, x ∈ D (called the domain) exactly one element y in a set E, y ∈ E (called the codomain or range).

The pair (x, y) is denoted as y = f(x) where: x is the independent variable (input) and y is the dependent variable (output). Often, both the domain D and codomain E are the set of real numbers ℝ or subsets of ℝ.

D is the domain, the set of all possible inputs. E is the codomain or range, the set of all possible outputs.

Key property💡: Each input has exactly one output. (No input is assigned two different outputs — this is the vertical line test!)

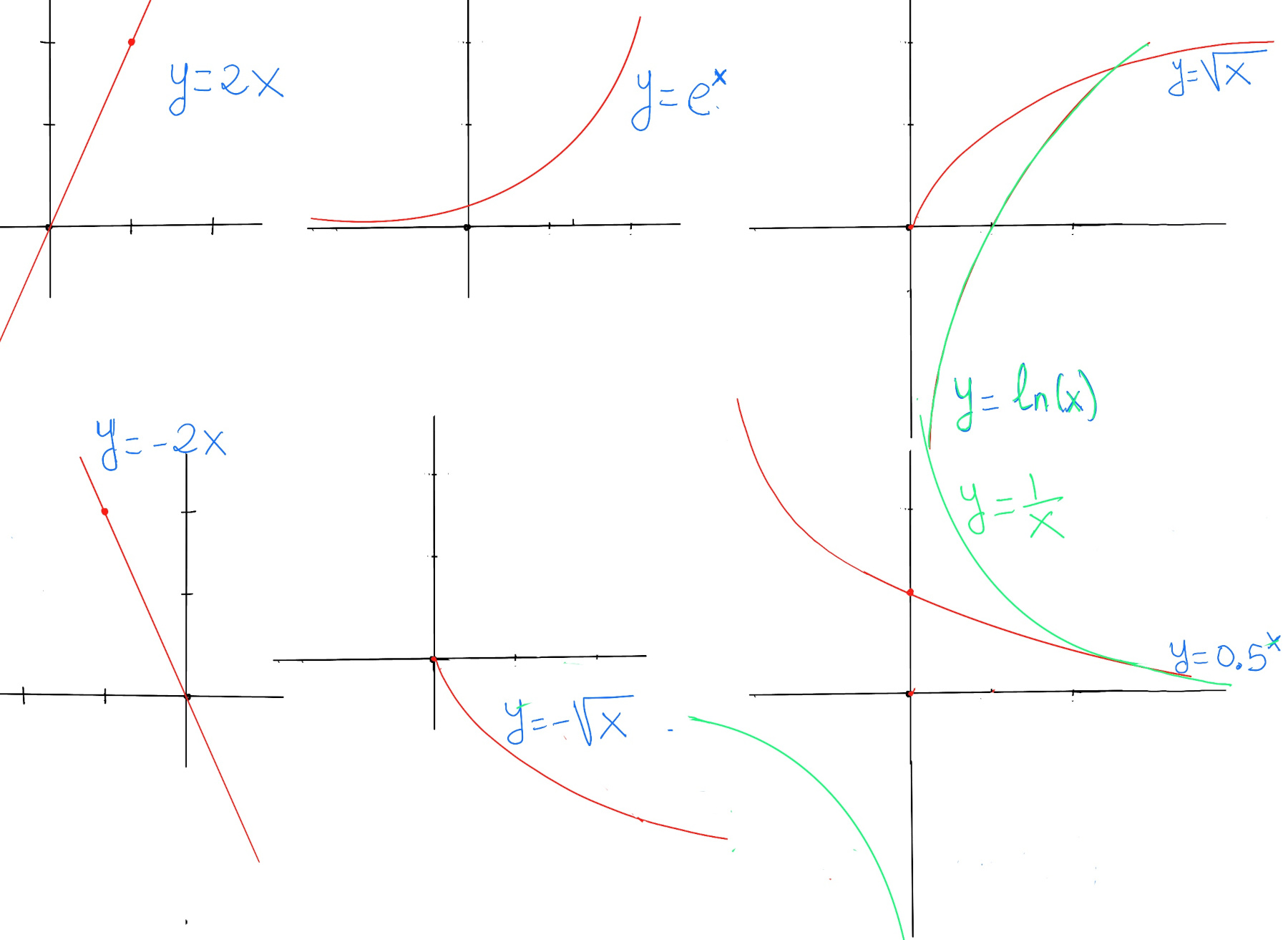

Examples: constant, f(x) = c, horizontal line, slope = 0; linear, f(x) = mx + b, straight line, constant slope m and y-intercept b; quadratic $f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c$, u-shaped or inverted U, opens up (a > 0) or down (a < 0), vertex at x = $\frac{-b}{2a}$, symmetry about vertical axis through vertex; polynomial, $f(x) = a_n x^n + \dots + a_0$, a smooth and continuous curve, n roots (counting multiplicity), end behaviour determined by its leading term $a_n x^n$; exponential function, $f(x) = a \cdot b^x, a \ne 0, b \gt 0$, rapid growth (b > 1) or decay (0 < b < 1); trigonometric functions, $\sin(x), \cos(x), \tan (z)$ oscillatory, periodic behavior (period 2π for sin/cos, π for tan), sin and cos are bounded between -1 and 1, but tan is unbounded; step function $f(x) = \lfloor x \rfloor$, greatest integer ≤ x, constant on intervals [n, n+1), jumps at integers, its graph is a staircase shape; absolute value f(x) = |x|, V-shaped graph, slope changes at 0.

Functions can be expressed in multiple forms, each useful in different contexts: verbal description, table of values (list of pairs), algebraic formula, graph, piecewise definition, recursive definition, parametric or integral form, and series representation.

Evaluating a function means finding or computing the output value f(x) for a given input value x. f(x) = $x^2-2x +4, f(2) = 2^2 -2\cdot 2 + 4 = 4 - 4 + 4 = 4, f(0) = 0^2 -2\cdot 0 + 4 = 4, f(1) = 1^2 -2\cdot 1 + 4 = 1 -2 +4 = 3$

The x-intercept is any point on the graph that intersects or crosses the x-axis. In other words, it is the value of x when the function (y-coordinate or y-value) is zero. The y-intercept is the point where the graph intersects or crosses the y-axis. y-coordinate of the point whose x-coordinate is 0, e.g., 2x - 3y = 6. x-intercept: set y = 0 → 2x = 6 ⇒ x=3, so (3, 0). y-intercept: set x = 0 → −3y = 6 ⇒ y = −2, so (0, −2).

Intuitively, a function is monotonic on an interval if it never changes its general direction on that interval: it either always goes up (or stays flat) as you move from left to right, or always goes down (or stays flat).

A monotonic function is a function that maintains a consistent direction of change on an interval of its domain: it is either entirely nondecreasing (monotone increasing) or entirely nonincreasing (monotone decreasing) on that interval. More precisely, let f be a real-valued function defined on some interval $I \subseteq \mathbb{R}$. f increases (or is nondecreasing) on an interval I if ∀a, b ∈ I, b > a ⟹ f(b) >= f(a). If, moreover, ∀a, b ∈ I, b > a ⟹ f(b) > f(a), the function f is said to be strictly increasing on I.

Increasing (nondecreasing): the function never goes down as you move from left to right along the x-axis, the graph either raises or stay flat. Strictly increasing: the function always goes up (strictly rises) as you move to the right; it never stays constant on any nontrivial interval.

Conversely, f decreases (or is nonincreasing) on an interval I if ∀a, b ∈ I, b > a ⟹ f(b) <= f(a). If ∀a, b ∈ I, b > a ⟹ f(b) < f(a), the function is said to be strictly decreasing on I.

Graphically, as you move from left to right along the x-axis, the graph either goes down or stays flat; for strictly decreasing, it always goes down.

Finally, f is said to be constant on an interval I if ∀a, b ∈ I, f(a) = f(b). In other words, the graph is a horizontal line on that interval.

If f is differentiable on I, monotonicity can often be detected via the derivative:

🧠 These results are consequences of the Mean Value Theorem. They make precise the intuition that a positive derivative means sloping upwards, the curve always climbs. Similarly, a negative derivative means sloping downwards, the curve always descends. Furthermore, a zero slope means the curve is flat.

We now turn to the study of local maxima and local minima, also called local extrema.

Informally, these are peaks and valleys of the graph when you look in a small neighborhood – the “highest” or “lowest” nearby point even if they are not the highest or lowest values on the entire domain.

Local extrema are the largest or smallest values locally, that is, in some interval around a point. More formally, they are points on the graph where the function reaches a maximum or minimum value within a small neighborhood around that point.

A critical point of a function f(x) is a point c in the domain where the derivative is zero (f’(c) = 0) or does not exists. Local extrema can only occur at critical points or at endpoints.

Let $D \subseteq \mathbb{R}$ be the domain of a function f and let c ∈ D.

Definition. f is said to have a local or relative maximum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≥ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$. That is, in some neighborhood around c, the value f(c) is at least as large as the nearby values of the function (the maximum value).

Definition. f is said to have a local or relative minimum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≤ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$. Again, in some neighborhood around c, the value f(c) is less than or equal to all the nearby values of the function (the minimum value).

We say that f has a local extremum at c if c is either a local maximum or a local minimum. Equivalently, it is a point where the function changes its monotonicity within the domain: from increasing to decreasing (local maximum) or from decreasing to increasing (local minimum).

Suppose f is defined on an interval I, and $c \in I$ is a point where f attains a local maximum or minimum. Then one of the following must hold:

Necessary condition: If f has a local extremum at an interior point (c is inside the domain, not at a boundary) where f' exists, then f'(c) = 0. However, a point where f’(c) = 0 (critical point) is not sufficient (does not guarantee) to be a local extremum, e.g., f(x) = $x^3-3x^2$, x = 0 is not a local extremum. Critical points may be a local maximum (peak), a local minimum (valley) or neither (inflection/saddle), e.g., $f(x)=x^3$ has f’(0) = 0, but no extremum at x = 0. This is a saddle point (or stationary point of inflection). Furthermore, extrema can occur at non-differentiable points (e.g., f(x) = |x| has a local minimum at x = 0, but f’(0) does not exist; f(x) = $\sqrt[3]{x^2}$ has a minimum at x = 0, but the derivative is undefined) or endpoints.

Conclusion: 💡Local extrema can only occur where the function stops rising or falling —either because the derivative is zero, the derivative doesn't exist, or you're at the edge of the domain.

Given f defined on an interval [a, b]: