Men lie, women lie, numbers don’t, Lil B

Recall

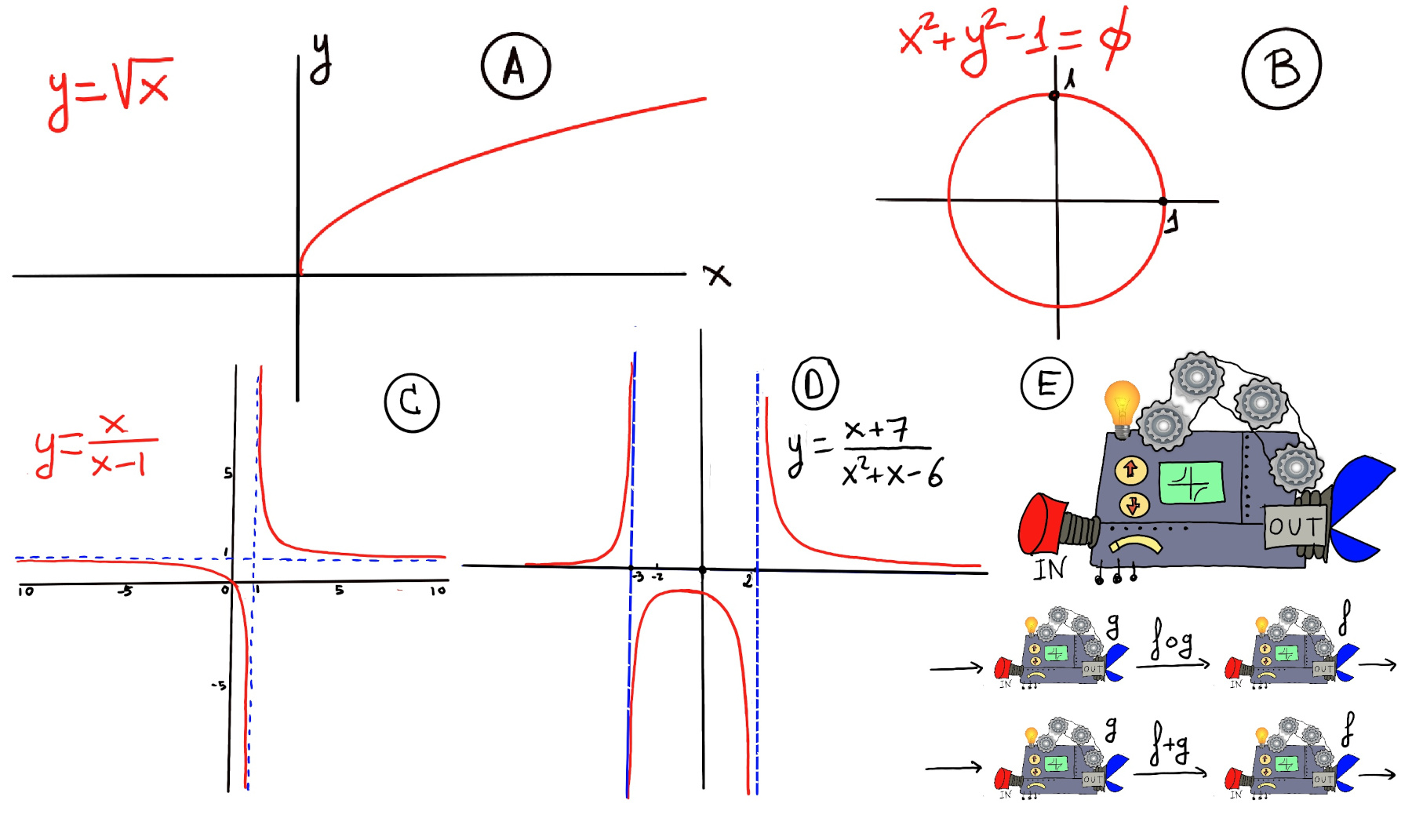

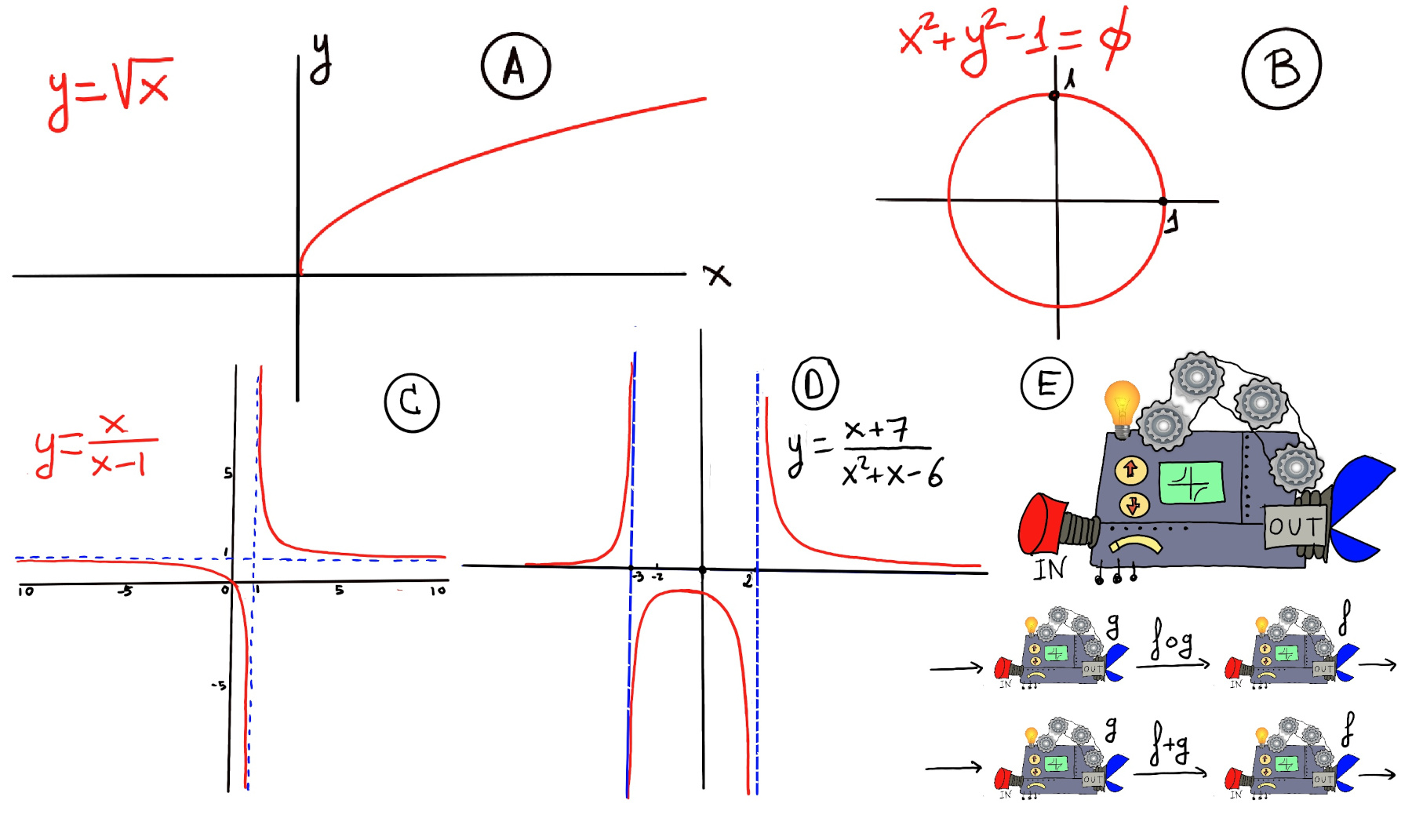

Definition. A function f is a rule, relationship, or correspondence that assigns to each element x in a set D, x ∈ D (called the domain) exactly one element y in a set E, y ∈ E (called the codomain or range). A mathematical function is like a black box that takes certain input values and generates corresponding output values (Figure E).

Very loosing speaking, a limit is the value to which a mathematical function gets closer and closer to as the input gets closer and closer to some given value.

A limit describe what is happening around a given point, say “a”. It is the value that the function approaches as the input approaches “a”, and it does not depend on the actual value of the function at a, or even on whether the function is defined at “a” at all.

Limits are essential to calculus and mathematical analysis and the understanding of how functions behave. The concept of a limit can be written or expressed as $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L.$ This notation is read as “the limit of f as x approaches a equals L”.

Intuitively, this means that the values of f(x) can be made arbitrarily close to L (and I mean as close as we like, e.g., L ± 0.1, L ± 0.01, L ± 0.001, and so on), by choosing values of x sufficiently close to a, but not necessarily equal to a.

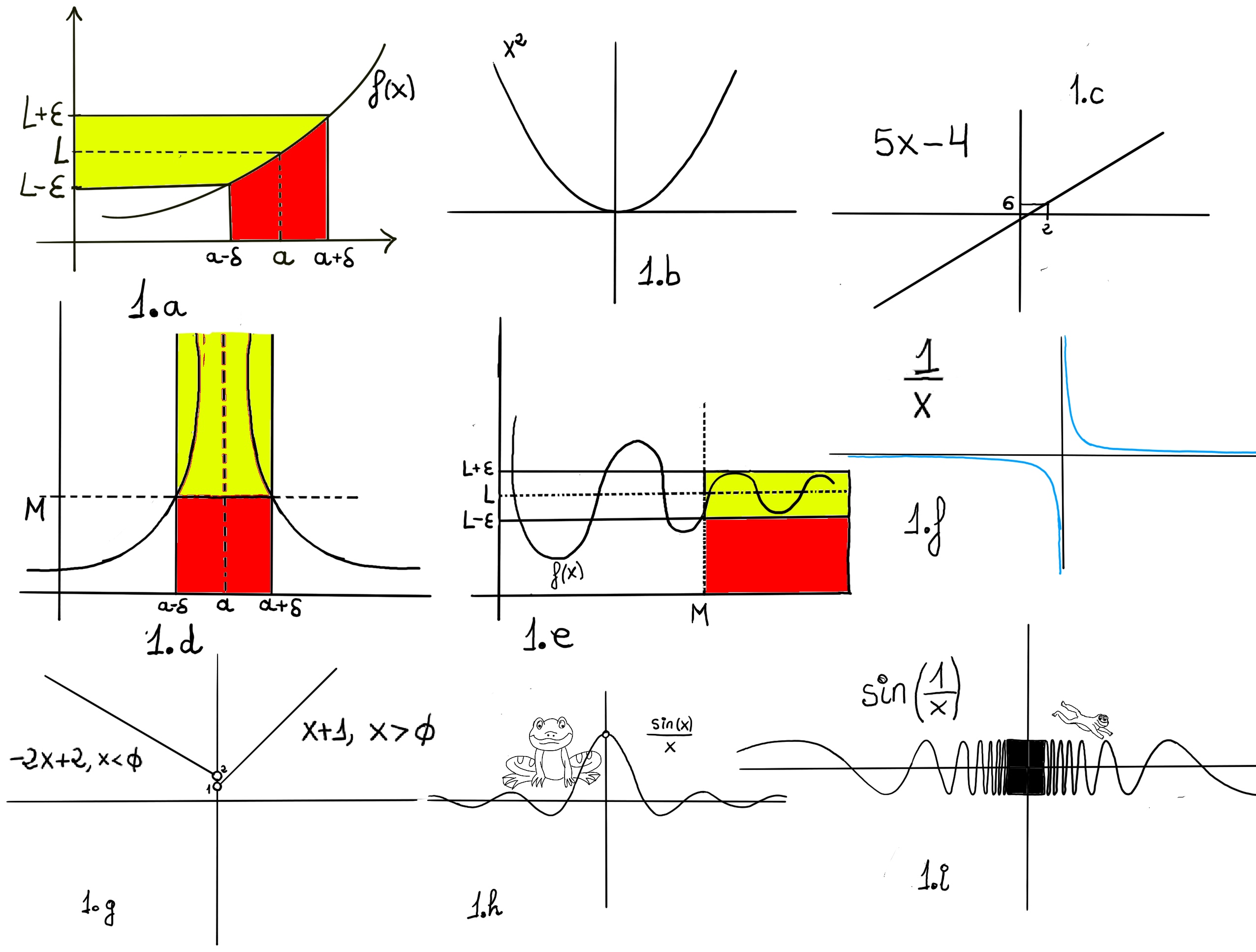

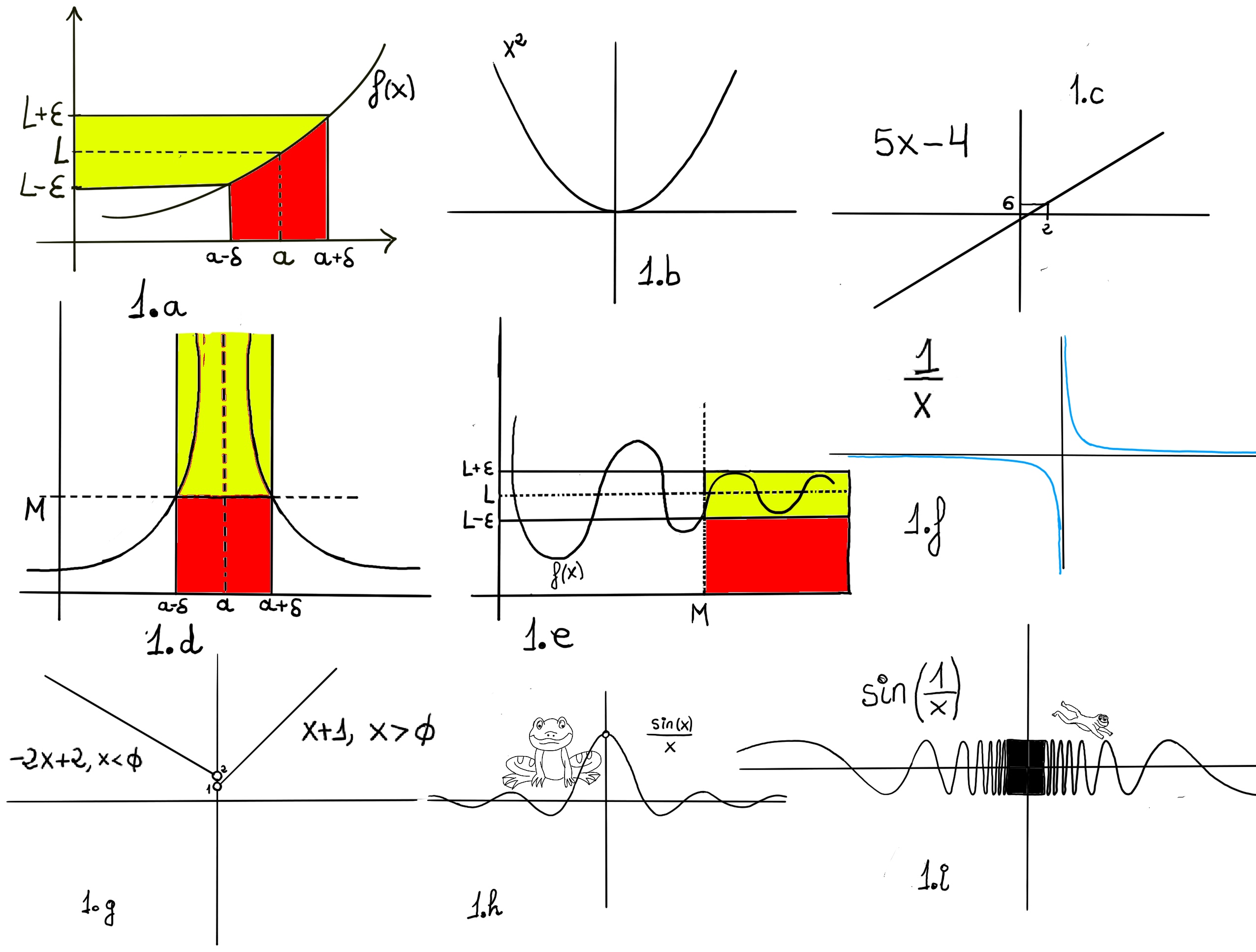

Formal definition. We say that the limit of f, as x approaches a, is L, and write $\lim_{x \to a}f(x) = L$. For every real ε > 0, there exists a real δ > 0 such that whenever 0 < | x − a | < δ we have | f(x) − L | < ε. In other words, we can make f(x) arbitrarily close to L, f(x)∈ (L-ε, L+ε) (within any distance ε > 0) by making x sufficiently close to a (within some distance δ > 0, but not equal to a) (x ∈ (a-δ, a+δ), x ≠ a) -Fig 1.a.-

Definition of Rational Functions

Definition. A rational function is any function that can be written as the ratio of two polynomial functions. Formally, a rational function f(x) is defined as f(x) = $\frac{p(x)}{q(x)} = \frac{a_nx^n+a_{n−1}x^{n−1}+…+a_1x+a_0}{b_mx^m+b_{m−1}x^{m−1}+…+b_1x+b_0}$ where p(x) and q(x) are polynomials with real coefficients; an ≠ 0, bm ≠ 0 (so the degrees of p and q are n and m respectively), and q(x) ≠ 0 to avoid division by zero, e.g., $\frac{3-2x}{x-2}, \frac{x^3 + x^2 - 2x + 12}{x+3}, \frac{3x^2-2}{x^2+5x+6}.$

The domain of a rational function consists of all real numbers except those that make the denominator zero, e.g., $f(x) = \frac{x^2-1}{x-1}$. Here, x = 1 is excluded from the domain, even though the expression simplifies algebraically to x + 1. Algebraic simplification does not change the domain of the original function; it only helps analyze behavior elsewhere.

Note that constant functions (e.g., f(x) = 5, which is $\frac{5}{1}$) and polynomials themselves (e.g., $f(x) = x^2$, which is $\frac{x^2}{1}$) are special cases of rational functions.

Limits of Rational Functions.

Limits describe the behavior of a function as $ x $ approaches a value a, written as $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)$. When computing $\lim_{x \to a} f(x)$ there are several standard strategies, depending on what happens when we substitute x = a.

- Direct substitution. The first step is to directly evaluate the function at the value that the independent variable approaches. If the function is defined at that point, we can obtain the limit value directly.

If a belongs to the domain of f (a ∈ Dom(f), i.e., $q(a) \ne 0$), the function is continuous at a, and the limit equals the function value f(a). Therefore, we substitute or plug the value into the expression directly.

- $\lim_{x \to 0} x^2 = 0$.

- $\lim_{x \to 2} 5x -4 = 5·2 -4 = 6$.

- $\lim_{x \to 1} \frac{3-2x}{x-2} = \frac{3-2}{1-2} = -1$.

- $\lim_{x \to 2} \frac{4x}{2x-3} = \frac{4·2}{4-3} = 8.$

- $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{x^2 + 3}{x + 1} = \frac{0 + 3}{0 + 1} = 3.$

- Indeterminate Form $\frac{0}{0}$. If a ∉ Dom(f) and substitution produces a zero in both denominator and numerator (substitution leads to an indeterminate form $\frac{0}{0}$), the limit may still exist. It sometimes works to factor the numerator and denominator, then simplify by canceling out common factors. After simplification, use direct substitution on the reduced form. A removable discontinuity corresponds to a canceled factor, revealing that the function behaves like a polynomial near a, except at the exact point.

- $\lim_{x \to 2}\frac{x^2-4}{x-2} =\lim_{x \to 2}\frac{(x+2)(x-2)}{x-2} = \lim_{x \to 2}x+2=4$.

- $\lim_{x \to 4} \frac{\sqrt{x}-2}{x-4} = \lim_{x \to 4} \frac{(\sqrt{x}-2)(\sqrt{x}+2)}{(x-4)(\sqrt{x}+2)} = \lim_{x \to 4} \frac{x-4}{(x-4)(\sqrt{x}+2)} = \lim_{x \to 4} \frac{1}{\sqrt{x}+2} = \frac{1}{4}.$

- $\lim_{x \to -4} \frac{x^2+3x-4}{x+4} = \lim_{x \to -4} \frac{(x-1)(x+4)}{x+4} = \lim_{x \to -4} (x-1) = -5$

- $\lim_{x \to 3} \frac{x^2-x-6}{x-3} = \lim_{x \to 3} \frac{(x+2)(x-3)}{x-3} = \lim_{x \to 3} (x+2) = 5$

- $\lim_{x \to -3} \frac{x^3 + x^2 - 2x + 12}{x+3} = \lim_{x \to -3} \frac{(x+3)(x^2-2x+4)}{x+3} = \lim_{x \to -3} (x^2-2x+4) = 9+6+4=19$

- Combining fractions. When the expression inside the limit contains sums or differences of rational expressions, it is often helpful to combine them into a single fraction over a common denominator. This can resolve indeterminate forms like $\infty - \infty$ or $\frac{0}{0}$.

- $\lim_{x \to 2} \frac{\frac{1}{x}-\frac{1}{2}}{x-2} = \lim_{x \to 2} \frac{\frac{2-x}{2x}}{x-2} = \lim_{x \to 2} \frac{-1}{2x} = \frac{-1}{4}$

- $\lim_{x \to 2}(\frac{1}{4x-8}-\frac{1}{x^2-4}) = \lim_{x \to 2} (\frac{1}{4(x-2)}-\frac{1}{(x-2)(x+2)}) = \lim_{x \to 2} (\frac{(x+2) - 4}{4(x-2)(x+2)}) = \lim_{x \to 2} \frac{x-2}{4(x-2)(x+2)} = \lim_{x \to 2} \frac{1}{4(x+2)} = \frac{1}{16}.$

- $\lim_{x \to 2} \frac{4}{x^2-4}-\frac{1}{x-2}$=[∞-∞] $\lim_{x \to 2} \frac{4-(x+2)}{(x-2)(x+2)} = \lim_{x \to 2} \frac{(2-x)}{(x-2)(x+2)} = \lim_{x \to 2} \frac{-1}{(x+2)} = \frac{-1}{4}.$

- The conjugate method (Rationalization). When the expression inside the limit involves radicals that cause an indeterminate form, it sometimes works to rationalize, that is, multiplying numerator and denominator by the conjugate that will get rid of the radical in the denominator (or numerator). Rationalization removes square roots and exposes cancelable factors,turning the expression into a rational form for easier evaluation.

Key conjugate pairs: $\sqrt{a}-b, \sqrt{a}+b; \sqrt{a}+b, \sqrt{a}-b; \sqrt{a}-\sqrt{b}, \sqrt{a}+\sqrt{b}$

- $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{\sqrt{1+x}-1}{x} = \lim_{x \to 0} \frac{\sqrt{1+x}-1}{x}·\frac{\sqrt{1+x}+1}{\sqrt{1+x}+1} = \lim_{x \to 0} \frac{(1+x)-1}{x(\sqrt{1+x}+1)} = \lim_{x \to 0} \frac{x}{x(\sqrt{1+x}+1)} = \lim_{x \to 0} \frac{1}{(\sqrt{1+x}+1)} = \frac{1}{2}$.

- $\lim_{x \to 0} (\frac{3}{x\sqrt{9-x}}-\frac{1}{x})$[Combine the fractions] $\lim_{x \to 0} (\frac{3-\sqrt{9-x}}{x\sqrt{9-x}}) = \lim_{x \to 0} (\frac{3-\sqrt{9-x}}{x\sqrt{9-x}}·\frac{3+\sqrt{9-x}}{3+\sqrt{9-x}}) = \lim_{x \to 0} \frac{9-(9-x)}{(x\sqrt{9-x})(3+\sqrt{9-x})} = \lim_{x \to 0} \frac{x}{(x\sqrt{9-x})(3+\sqrt{9-x})} = \lim_{x \to 0} \frac{1}{(\sqrt{9-x})(3+\sqrt{9-x})} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{9}(3+\sqrt{9})} = \frac{1}{3·6} = \frac{1}{18}$

- $\lim_{x \to 2} \frac{3-\sqrt{2x+5}}{x-2} = \lim_{x \to 2} \frac{3-\sqrt{2x+5}}{x-2}\frac{3+\sqrt{2x+5}}{3+\sqrt{2x+5}} = \lim_{x \to 2} \frac{9-(2x+5)}{(x-2)(3+\sqrt{2x+5})} = \lim_{x \to 2} \frac{-2x+4}{(x-2)(3+\sqrt{2x+5})} = \lim_{x \to 2} \frac{-2(x-2)}{(x-2)(3+\sqrt{2x+5})} = \lim_{x \to 2} \frac{-2}{(3+\sqrt{2x+5})} = \frac{-2}{3+\sqrt{9}} = \frac{-2}{6} = \frac{-1}{3}$

- $\lim_{x \to 9} \frac{x-9}{\sqrt{x}-3} = \lim_{x \to 9} \frac{(x-9)(\sqrt{x}+3)}{(\sqrt{x}-3)(\sqrt{x}+3)} = \lim_{x \to 9} \frac{(x-9)(\sqrt{x}+3)}{x-9} = \lim_{x \to 9} \sqrt{x}+3 = \sqrt{9} + 3 = 6.$

- $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{1}{x\sqrt{x+1}}-\frac{1}{x} =$ [∞-∞] $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{1-\sqrt{x+1}}{x\sqrt{x+1}} = \lim_{x \to 0} \frac{1-\sqrt{x+1}}{x\sqrt{x+1}} \frac{1+\sqrt{x+1}}{1+\sqrt{x+1}} = \lim_{x \to 0} \frac{1-(x+1)}{x\sqrt{x+1}(1+\sqrt{x+1})} = \lim_{x \to 0} \frac{-x}{x\sqrt{x+1}(1+\sqrt{x+1})} = \lim_{x \to 0} \frac{-1}{\sqrt{x+1}(1+\sqrt{x+1})} = \frac{-1}{2}$

- $\lim_{x \to 3}\frac{\sqrt{x+1}-2}{x-3} = \lim_{x \to 3}\frac{\sqrt{x+1}-2}{x-3}\cdot \frac{\sqrt{x+1}+2}{\sqrt{x+1}+2} = lim_{x \to 3} \frac{x + 1 -4}{(x -3)(\sqrt{x+1}+2)} = lim_{x \to 3} \frac{x -3}{(x -3)(\sqrt{x+1}+2)} = lim_{x \to 3} \frac{1}{\sqrt{x+1}+2} = \frac{1}{4}$

- $\lim_{x \to 4} \frac{\sqrt{x} - 2}{x - 4} = \lim_{x \to 4} \frac{(\sqrt{x} - 2)(\sqrt{x} + 2)}{(x - 4)(\sqrt{x} + 2)} = \lim_{x \to 4} \frac{x - 4}{(x - 4)(\sqrt{x} + 2)} = \lim_{x \to 4} \frac{1}{\sqrt{x} + 2} = \frac{1}{4}$.

- Non-Zero Over Zero — Vertical Asymptotes. If direct substitution yields $\frac{c}{0}$ where c ≠ 0, then the limit does not exist as a finite number. Instead, the function exhibits unbounded behavior as x approaches a. If both one-sided limits are the same, we say $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = ∞,~or~ \lim_{x \to a} f(x) = -∞$ meaning that the limit does not exist, but we know the function is growing infinitely large or small. This situation typically indicates a vertical asymptote at x = a.

Step-by-Step Analysis:

- Identify the one-sided limits. Evaluate $\lim_{x \to a^-} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}$ and $\lim_{x \to a^+} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}$ separately.

- Determine the sign of the denominator. Check whether g(x) approaches 0 from the positive side ($g(x) \to 0^+$) or the negative side ($g(x) \to 0^-$) as x approaches a from each direction.

- Combine with the sign of the numerator. The sign of the limit is given by: $\frac{\text{sign of f(x)}}{\text{sign of g(x)}}$

- Interpret the result. If both one-sided limits are +∞ (or both −∞), then the two-sided limit is also positive (or negative) infinite. If the one-sided limits have opposite signs (one +∞, the other −∞), then the two-sided limit does not exist.

Examples:

- Consider $\lim_{x \to 2} \frac{x + 1}{x -2}$. Direct substitution gives $\frac{3}{0}$, non-zero over zero. We need to analyze both one-sided limits, $\lim_{x \to 2^+} \frac{x + 1}{x -2} = \infty, \lim_{x \to 2^-} \frac{x + 1}{x -2} = -\infty$. Since the one-sided limits are infinite but opposite, the two-sided limit does not exist. However, there is a vertical asymptote at x = 2.

- $\lim_{x \to 1} \frac{-4}{(x-1)^2}$. Direct substitution gives $\frac{-4}{0}$, non-zero over zero. The denominator $(x-1)^2$ is always non-negative and approaches 0 from the positive side from both directions. Therefore, $\lim_{x \to 1} \frac{-4}{(x-1)^2} = -\infty$. Vertical asymptote at x = 1.

- $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{1}{x^2} = ∞$ because $\lim_{x \to 0⁺} \frac{1}{x^2} = \lim_{x \to 0⁻} \frac{1}{x^2} = ∞$.

- $\lim_{x \to 2} \frac{x^2+4}{x^3-8}$ does not exist because $\lim_{x \to 2⁺} \frac{x^2+4}{x^3-8} = \frac{8}{0⁺} = ∞, \lim_{x \to 2⁻} \frac{x^2+4}{x^3-8} = \frac{8}{0⁻} = -∞$.

- $\lim_{x \to 3} \frac{x-4}{x^2-6x+9} = \lim_{x \to 3} \frac{x-4}{(x-3)^2} = -∞$.

Limits at infinite

The value of $\lim_{x \to \pm\infty} f(x)$ can be determined by dividing the numerator and denominator by the highest power of x appearing in the denominator. At infinity, the highest-degree terms dominate the behavior of the function.

Method: Divide by the Highest Power of x appearing in the denominator, e.g., $\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{2x^2}{(x^2+1)(x-3)} = \lim_{x \to ∞}\frac{2x^2}{x^3-3x^2+x-3}$ =[Apply L’Hôpital’s rule or divide by x3] = $\lim_{x \to ∞}\frac{\frac{2}{x}}{1-3\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{x^2}-3\frac{1}{x^3}} = 0$; $\lim_{x \to -∞} \frac{7x^3-x+2}{2x^2-5x-6}$ =[Apply L’Hôpital’s rule or divide by x2] = $\lim_{x \to -∞}\frac{7x-\frac{1}{x}+\frac{2}{x^2}}{2-\frac{5}{x}-\frac{6}{x^2}} = -∞$; $\lim_{x \to -∞} \frac{7x^3-x+2}{2x^3-5x-6}$ =[Apply L’Hôpital’s rule or divide by x3] = $\lim_{x \to -∞}\frac{7-\frac{1}{x^2}+\frac{2}{x^3}}{2-\frac{5}{x^2}-\frac{6}{x^3}} = \frac{7}{2}$.

The limits at infinity for a rational function, say f(x) = $\frac{p(x)}{q(x)} = \frac{a_nx^n+a_{n−1}x^{n−1}+…+a_1x+a_0}{b_mx^m+b_{m−1}x^{m−1}+…+b_1x+b_0}$ can be exclusively determined or calculated based on its degrees:

- The degree of the numerator and the denominator are the same, $\lim_{x \to ∞} f(x) = \lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{a_nx^n+a_{n−1}x^{n−1}+…+a_1x+a_0}{b_mx^m+b_{m−1}x^{m−1}+…+b_1x+b_0} = \frac{a_n}{b_m}$ where m = n, an and bn = bm are the leading coefficients of p and q respectively. The line $ y = \frac{a_n}{b_m}$ is a horizontal asymptote.

- $\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{2x^7+4x^3+2x+1}{3x^7+4x^2+3x+5} = \lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{2x^7}{3x^7} = \lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{2}{3} = \frac{2}{3}.$

- $\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{4x^2+2x+7}{3x^2+3x+2} = \frac{4}{3}.$

- $\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{2x^5+3x^4+2x^3+7x+1}{2x^5+12x^4+3x^2+2x+8} = 1.$

- The degree of the numerator is smaller than the degree of the denominator, $\lim_{x \to ∞} f(x) = \lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{a_nx^n+a_{n−1}x^{n−1}+…+a_1x+a_0}{b_mx^m+b_{m−1}x^{m−1}+…+b_1x+b_0} = 0$. The line y = 0 is a horizontal asymptote.

- $\lim_{x \to ±∞} \frac{2x^6+4x^3+2x+1}{3x^7+4x^2+3x+5} = \lim_{x \to ±∞} \frac{2x^6}{3x^7} = \lim_{x \to ±∞} \frac{2}{3x} = 0.$

- $\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{4x^2+2x+7}{3x^3+3x+2} =0.$

- $\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{2x^5+3x^4+2x^3+7x+1}{2x^7+2x^4+3x^2+2x+8} = 0.$

- The degree of the numerator is bigger than the degree of the denominator, $\lim_{x \to ∞} f(x) = \lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{a_nx^n+a_{n−1}x^{n−1}+…+a_1x+a_0}{b_mx^m+b_{m−1}x^{m−1}+…+b_1x+b_0} = ±∞$. No horizontal asymptote. The graph may have a slant (oblique) asymptote.

- $\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{2x^5+8x^2+8}{9x^3+4x^2+3x+5} = \lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{2x^5}{9x^3} = \lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{2x^2}{9} = ∞.$

- $\lim_{x \to -∞} \frac{4x^3+2x+7}{3x^2+3x+2} = \lim_{x \to -∞} \frac{4x^3}{3x^2} = \lim_{x \to -∞} \frac{4x}{3} = -∞.$

- $\lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{4x^3+2x+7}{3x^2+3x+2} = \lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{4x^3}{3x^2} = \lim_{x \to ∞} \frac{4x}{3} = ∞.$

Bibliography

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

- NPTEL-NOC IITM, Introduction to Galois Theory.

- Algebra, Second Edition, by Michael Artin.

- LibreTexts, Calculus.

- Field and Galois Theory, by Patrick Morandi. Springer.

- Michael Penn, and MathMajor.

- Contemporary Abstract Algebra, Joseph, A. Gallian.

- YouTube’s Andrew Misseldine: Calculus, College Algebra and Abstract Algebra.

- Calculus Early Transcendentals: Differential & Multi-Variable Calculus for Social Sciences.

- blackpenredpen.