|

|

|

Trigonometry is a “sine” of the times, Anonymous.

Trigonometry is the foundation upon which calculus stands tall.

The derivative of a function at a specific input value describes the instantaneous rate of change. Geometrically, when the derivative exists, it is the slope of the tangent line to the graph of the function at that point. Algebraically, it represents the ratio of the change in the dependent variable to the change in the independent variable as the change approaches zero.

Definition. A function f(x) is differentiable at a point “a” in its domain, if its domain contains an open interval around “a”, and the following limit exists $f'(a) = L = \lim _{h \to 0}{\frac {f(a+h)-f(a)}{h}}$. More formally, for every positive real number ε, there exists a positive real number δ, such that for every h satisfying 0 < |h| < δ, then the following inequality holds |L-$\frac {f(a+h)-f(a)}{h}$|< ε.

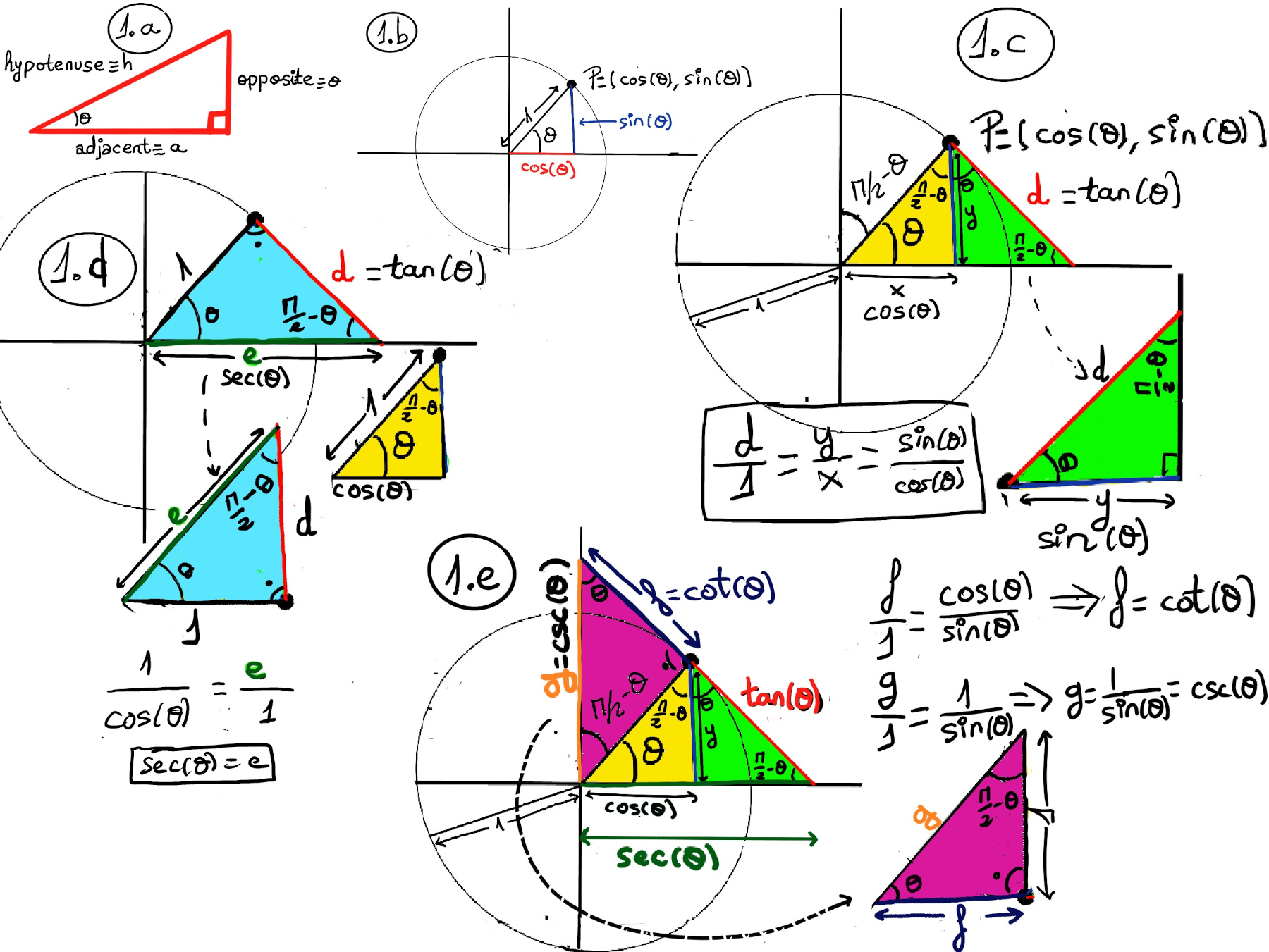

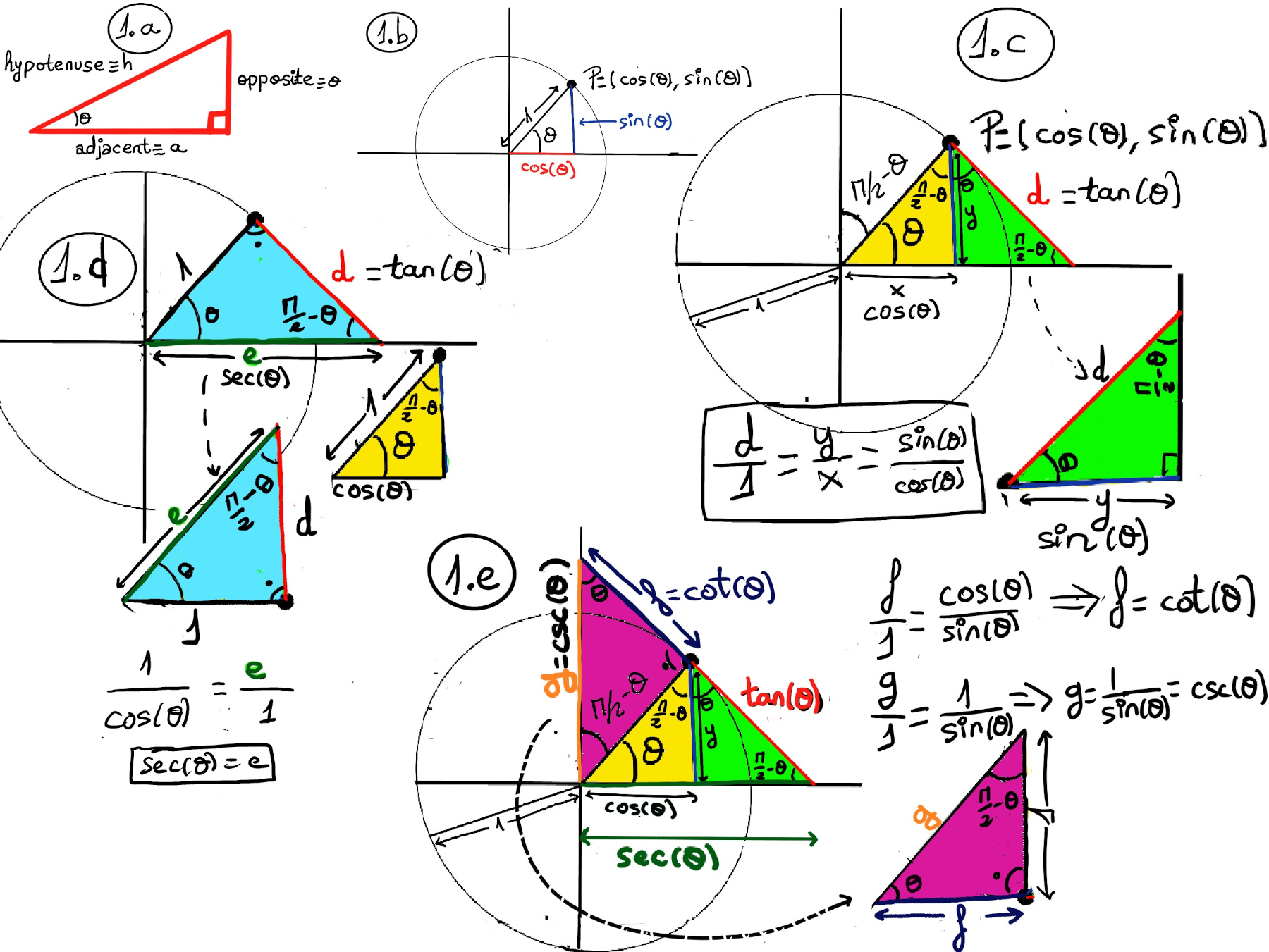

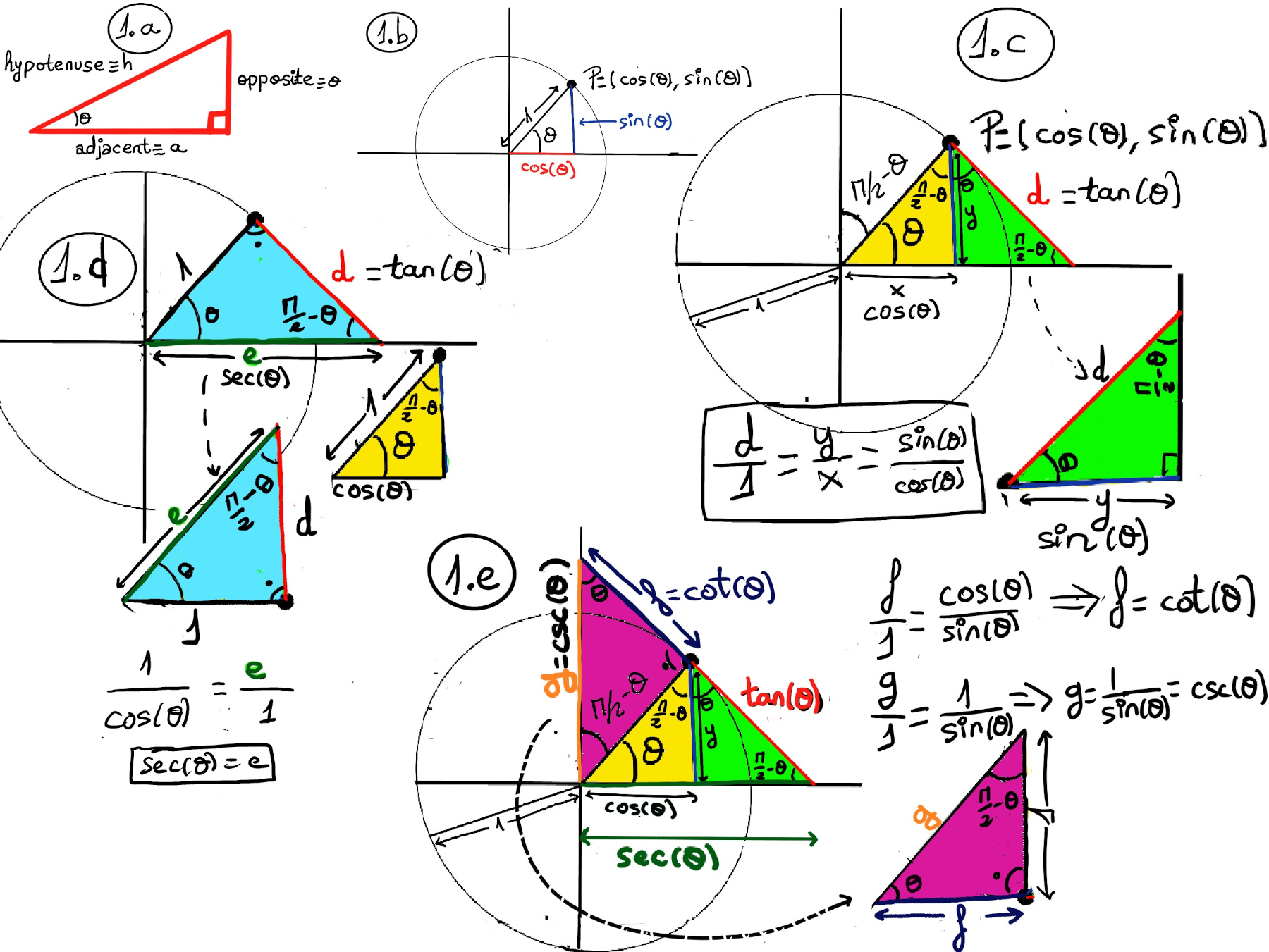

A triangle is a closed planar (2-dimensional) figure with three sides, three angles, and three vertices. It is a three-sided polygon and the sum of its interior angles is always α + β + γ = $180^\circ = \pi$ radians. It is one of the most basic shapes in geometry and is denoted by the symbol △. We often work with right triangles (one angle equals $90^\circ = \frac{\pi}{2}$). In a right triangle, the side opposite the right angle is the hypotenuse (the longest side); the other two sides are called the adjacent and opposite with respect to a chosen non-right angle.

For a given acute angle θ in a right triangle, we define three primary trigonometric ratios:

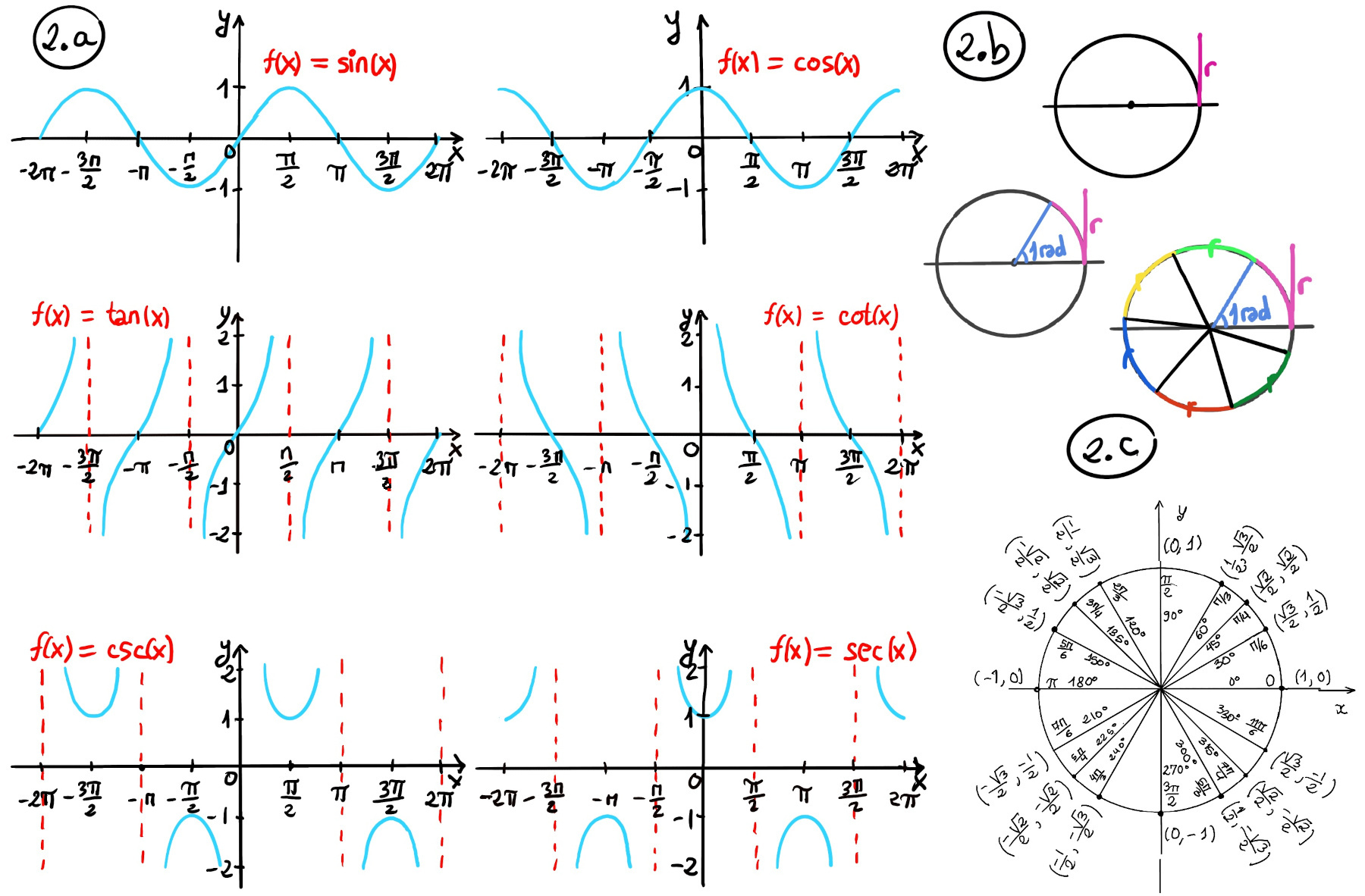

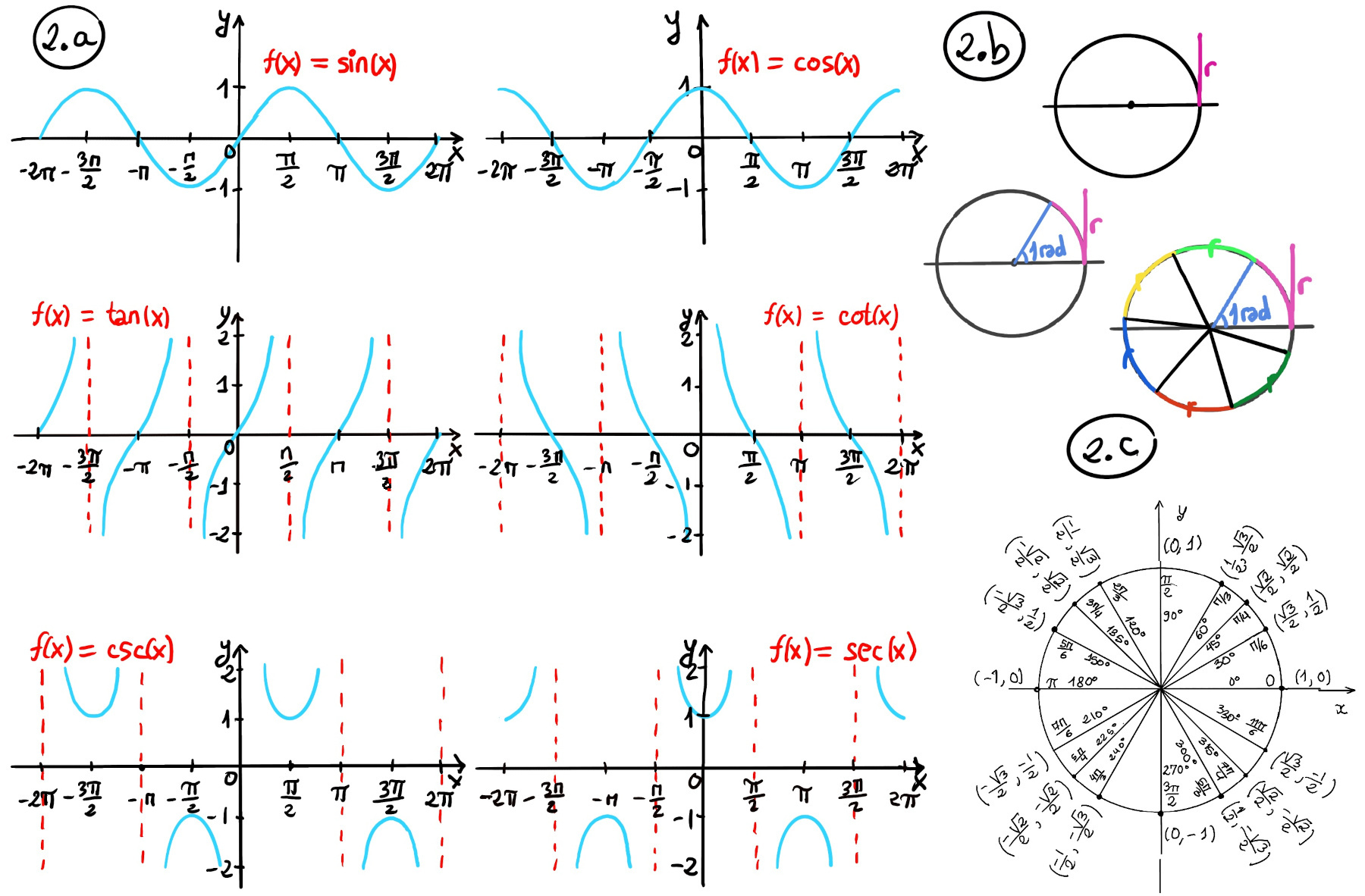

The sine function is the ratio of the length of the side opposite the angle and the length of the hypotenuse, $sin(θ) = \frac{opposite}{hypotenuse} = \frac{o}{h}$. It is odd (sin(-x) = -sin(x), the graph is symmetric with respect to the origin), periodic with a period of 2π, and it ranges between -1 and 1 (Figure 1.a.).

The cosine function is the ratio of the length of the side adjacent to the angle and the length of the hypotenuse, $cos(θ) = \frac{adjacent}{hypotenuse} = \frac{a}{h}$. It is even (cos(-θ) = cos(θ), the graph is symmetric about the y- or the vertical axis), periodic with a period of 2π, and its range is between -1 and 1.

The tangent function is the ratio of the length of the opposite side and the length of the adjacent side, $tan(θ) = \frac{opposite}{adjacent} = \frac{o}{a}$. It is an odd function (tan(-x) = -tan(x)). The domain of the tangent function is all real numbers, except at x-values where there are vertical asymptotes, namely x = $\frac{π}{2} +nπ = \frac{(π+(nπ2))}{2} = \frac{(2n+1)π}{2}$ where n ∈ ℤ. The range of the tangent function is all real numbers.

Three additional functions are defined as reciprocals of the primary ones:

Their domains exclude values where the denominator is zero.

Mnemonic. Easy way to remember this trigonometrical ratios is with the Mnemonic SOH-CAH-TOA, meaning Sine is Opposite over the Hypotenuse, Cosine is Adjacent over the Hypotenuse, and Tangent is Opposite over the Adjacent.

sin and cos are smooth, continuous, periodic waves; period: 2π (repeats every 360⁰); range: [-1, 1] (bounded between maxima +1 and minima −1); no discontinuities, defined for all real numbers. tan: a repeating curve that shoots up to +∞ and down from −∞; period: π (repeats every 180⁰), range: (−∞,∞) (unbounded), passes through the origin and has vertical asymptotes where cos(θ)=0 ($\frac{(2n+1)\pi}{2}$).

Consider the unit circle, i.e., a circle centered at the origin with radius one unit. Denote its center (0,0) as O, and denote the point (1,0) on it as A. As a moving point B travels around the unit circle starting at A and moving in a counterclockwise direction, the angle AOB increases. When B has made it all the way around the circle and back to A, the angle has increased by 360° (or $2\pi$ radians), but the terminal side is the same. Therefore, sine and cosine are periodic with period 360° (or $2\pi$ radians). In other words, for any arbitrary angle θ, $sin(θ+360°) = sin(θ), cos(θ+360°) = cos(θ)$ or equivalently, $sin(θ+2π) = sin(θ), cos(θ+2π) = cos(θ)$. Degrees and radians: $360^\circ = 2\pi, 180^\circ = \pi$.

In the unit circle, the sine function represents the y-coordinate and the cosine function represents the x-coordinate of any point. Hence, each angle $\theta$ corresponds to a point P(θ) = (cos(θ), sin(θ)) where $\cos(\theta)$ is the x-coordinate and $\sin(\theta)$ is the y-coordinate of the point where the terminal side of the angle meets the circle (Figure 1.b.).

Recall that Cartesian coordinates are used to uniquely identify points in a two-dimensional plane by their distances from two perpendicular lines called the x-axis and the y-axis. The plane is divided into four quadrants based on the signs of the coordinates, namely Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4, e.g., the upper-right quadrant where both the x and y coordinates are positive is Q1.

In the first quadrant, the right triangle formed by the radius, the x-axis, and the vertical line through P has acute angles $\theta$ and $\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta$ (yellow triangle, figure 1.c.) ⇒ $cos(θ) = sin(\frac{π}{2}-θ)$. Angles $\theta$ and $\tfrac{\pi}{2}-\theta$ are complementary. On the unit circle or in a right triangle: $cos(\theta)=\sin \left(\tfrac{\pi}{2}-\theta\right), \sin(\theta)=\cos\left(\tfrac{\pi}{2}-\theta\right).$

Next, we draw a line that is tangent to the circle at P(cos(θ), sin(θ)) and perpendicular to the radius, and let’s name the line segment d, and we can observe that we have two similar triangles (yellow and green triangles are similar triangles because they have the same angles, namely $\pi, \theta, \frac{π}{2}-\theta$, figure 1.c).

Similar triangles are triangles that are the same shape but not necessarily the same size. Similar triangles are triangles whose corresponding angles are equal and whose corresponding sides are proportional but not necessarily equal.

Therefore, $\frac{d}{1} = \frac{y}{x} = \frac{sin(θ)}{cos(θ)} ⇒ d = tan(θ)$

Similarly, the blue and yellow triangles are similar (Figure 1.d) ⇒ $\frac{1}{cos(θ)} = \frac{e}{1} ⇒ sec(θ) = e.$ Recall that the secant is the reciprocal of the cosine. Finally, we draw a perpendicular line to the radius that is tangent to the circle at P and connects to the y-axis and the reader may realize that the pink and yellow triangles are similar (Figure 1.e) ⇒ $\frac{f}{cos(θ)} = \frac{1}{sin(θ)} ↭ \frac{f}{1} = \frac{cos(θ)}{sin(θ)} = cot(θ) ⇒ f = cot(θ), \frac{g}{1} = \frac{1}{sin(θ)} ⇒ g = \frac{1}{sin(θ)} = csc(θ)$. Recall that cotangent is the reciprocal of the tangent, i.e., the ratio of the adjacent side to the opposite side in a right triangle. Besides, the cosecant is the reciprocal of the sine.

By the Pythagorean theorem in the yellow triangle, we obtain that $sin^2(θ)+cos^2(θ) = 1.$ By the Pythagorean theorem in the yellow+green triangle, $1+tan^2(θ) = sec^2(θ),$ and in the pink triangle, $1+cot^2(θ) = csc^2(θ).$

A radian is the angle subtended at the centre of a circle by an arc that is equal in length to the radius of the circle. The length of a circumference is given by the following expression: l =[d is the diameter] π·d = 2·π·r. If you take the circumference of a circle and divide it by its radius ($\frac{l}{r} = 2·π$), you get 2π radians (or approximately 6.28318 radians) for one complete revolution ≈ 6 rad + 0.28318 (Figure 2.b): $\pi \text{ rad} = 180° \implies 1 \text{ rad} = \frac{180°}{\pi} \approx 57.2958°$

θ (in radians) = $\frac{\text{arc length}}{\text{radius}} = \frac{s}{r}$

| Conversion | Formula |

|---|---|

| Degrees → Radians | $\quad \theta_{rad} = \theta_{deg} \times \dfrac{\pi}{180°}$ |

| Radians → Degrees | $\quad \theta_{deg} = \theta_{rad} \times \dfrac{180°}{\pi}$ |

Besides, on the unit circle (radius = 1), for any angle θ: (cos(θ), sin(θ)) = coordinates of the point on the circle. An angle of π radians corresponds to halfway around the circle (180 degrees), an angle of 2π radians corresponds to one complete revolution (360 degrees) -Figure 2.c.-, and various fractions of π corresponds to different angles, e.g., 30° is π/6, 45° is π/4, 60° is π/3, 90° is π/2 and so on.

Let’s calculate sin(30°) and cos(30°) (Figure 3.b).

Let’s calculate sin(45°) and cos(45°) (Figure 3.c).

Deriving sin(60°) and cos(60°). Using the complementary angle relationship:

$\sin(60°) =[\sin(\theta) = \cos(90° - \theta)] \cos(30°) = \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$ and $\cos(60°) =[\cos(\theta) = \sin(90° - \theta)] \sin(30°) = \frac{1}{2}$

For a circle with radius $r$ and central angle $\theta$ (in radians):

The *Hand Trick Pattern. For angles 0°, 30°, 45°, 60°, 90°: $\sin\theta = \frac{\sqrt{n}}{2} \quad \text{where } n = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4$

| Angle | $\sin\theta$ | $\cos\theta$ | $\tan\theta$ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0° $(0)$ | $0$ | $1$ | $0$ |

| 30° $\left(\dfrac{\pi}{6}\right)$ | $\dfrac{1}{2}$ | $\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$ | $\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{3}} = \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{3}$ |

| 45° $\left(\dfrac{\pi}{4}\right)$ | $\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}$ | $\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}$ | $1$ |

| 60° $\left(\dfrac{\pi}{3}\right)$ | $\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$ | $\dfrac{1}{2}$ | $\sqrt{3}$ |

| 90° $\left(\dfrac{\pi}{2}\right)$ | $1$ | $0$ | undefined |

These formulas form the foundation for solving triangles, simplifying expressions, and analyzing periodic phenomena.

$\textbf{Basic Trigonometric Identities:}$

$sin^2(x) + \cos^2(x) = 1, 1 + \tan^2(x) = \sec^2(x), 1 + \cot^2(x) = \csc^2(x).$

$\textbf{Angle Sum and Difference Formulas:}$

$sin(A \pm B) = \sin A \cos B \pm \cos A \sin B, \cos(A \pm B) = \cos A \cos B \mp \sin A \sin B, \tan(A \pm B) = \frac{\tan A \pm \tan B}{1 \mp \tan A \tan B}.$

$\textbf{Double Angle Formulas:}$

$\sin(2x) = 2\sin x \cos x, \cos(2x) = \cos^2 x - \sin^2 x = 1 -2\sin^2 x = 2\cos^2 x -1, \tan(2x) = \frac{2\tan x}{1 - \tan^2 x}.$

$\textbf{Half Angle Formulas:}$

$\sin\left(\frac{x}{2}\right) = \pm \sqrt{\frac{1 - \cos x}{2}},\cos\left(\frac{x}{2}\right) = \pm \sqrt{\frac{1 + \cos x}{2}}, \tan\left(\frac{x}{2}\right) = \frac{\sin x}{1 + \cos x}$.

$\textbf{Product-to-Sum Formulas:}$

$\sin A \sin B = \frac{1}{2} [\cos(A - B) - \cos(A + B)], \cos A \cos B = \frac{1}{2} [\cos(A - B) + \cos(A + B)], \sin A \cos B = \frac{1}{2} [\sin(A + B) + \sin(A - B)], \cos A \sin B = \frac{1}{2} [\sin(A + B) - \sin(A - B)]$

$\textbf{Sum-to-Product Formulas:}$

$\sin A + \sin B = 2\sin\left(\frac{A + B}{2}\right)\cos\left(\frac{A - B}{2}\right), \sin A - \sin B = 2\sin\left(\frac{A - B}{2}\right)\cos\left(\frac{A + B}{2}\right), \cos A + \cos B = 2\cos\left(\frac{A + B}{2}\right)\cos\left(\frac{A - B}{2}\right), \cos A - \cos B = -2\sin\left(\frac{A + B}{2}\right)\sin\left(\frac{A - B}{2}\right).$

To find derivatives of trigonometric functions, we use the limit definition of the derivative: $\frac{sin(x+h) -sin(x)}{h} =$ [The key identity is sin(a+b) = sin(a)cos(b) + cos(a)sin(b)] $\frac{sin(x)cos(h) + cos(x)sin(h) -sin(x)}{h} =[\text{Rearrange terms}] sin(x)(\frac{cos(h)-1}{h}) + cos(x)(\frac{sin(h)}{h})$

$lim_{h \to 0} \frac{sin(x+h) -sin(x)}{h} = lim_{h \to 0} sin(x)(\frac{cos(h)-1}{h}) + cos(x)(\frac{sin(h)}{h}) = $

Apply essential limits from calculus: $\lim_{x \to 0} (\frac{sin(x)}{x}) = 1$ and $\lim_{x \to 0} (\frac{1-cos(x)}{x}) = 0$ (which implies $\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{cos(h)-1}{h} = (-1)·0$) and limit laws, we get:

$ = (-1)·0·sin(x) + cos(x)*1 = cos(x) $

$\frac{cos(x+h) -cos(x)}{h} =$ [Recall the identity cos(a+b) = cos(a)cos(b) - sin(a)sin(b)] $\frac{cos(x)cos(h) - sin(x)sin(h) -cos(x)}{h} =[\text{Rearrange terms: }] cos(x)(\frac{cos(h)-1}{h}) - sin(x)(\frac{sin(h)}{h})$

Apply the same limits $\lim_{x \to 0} (\frac{sin(x)}{x}) = 1$ and $\lim_{x \to 0} (\frac{1-cos(x)}{x}) = 0$ and limit laws:

$ = cos(x)·-1·0 -sin(x)·1 = -sin(x).$

$\frac{d}{dx}\frac{sinx}{cosx}$ =[Quotient Rule] $\frac{cosxcosx+sinxsinx}{cos^{2}x} = \frac{1}{cos^{2}x} =sec^2(x)$