|

|

|

Now is the time for us to shine. The time when our dreams are within reach and possibilities vast. Now is the time for all of us to become the people we have always dreamed of being. This is your world. You’re here. You matter. The world is waiting, Haley James Scott.

Definition. A function f is a rule, relationship, or correspondence that assigns to each element x in a set D, x ∈ D (called the domain) exactly one element y in a set E, y ∈ E (called the codomain or range).

The pair (x, y) is denoted as y = f(x) where: x is the independent variable (input) and y is the dependent variable (output). Often, both the domain D and codomain E are the set of real numbers ℝ or subsets of ℝ.

D is the domain, the set of all possible inputs. E is the codomain or range, the set of all possible outputs.

Key property💡: Each input has exactly one output. (No input is assigned two different outputs — this is the vertical line test!)

Examples: constant, f(x) = c, horizontal line, slope = 0; linear, f(x) = mx + b, straight line, constant slope m and y-intercept b; quadratic $f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c$, u-shaped or inverted U, opens up (a > 0) or down (a < 0), vertex at x = $\frac{-b}{2a}$, symmetry about vertical axis through vertex; polynomial, $f(x) = a_n x^n + \dots + a_0$, a smooth and continuous curve, n roots (counting multiplicity), end behaviour determined by its leading term $a_n x^n$; exponential function, $f(x) = a \cdot b^x, a \ne 0, b \gt 0$, rapid growth (b > 1) or decay (0 < b < 1); trigonometric functions, $\sin(x), \cos(x), \tan (z)$ oscillatory, periodic behavior (period 2π for sin/cos, π for tan), sin and cos are bounded between -1 and 1, but tan is unbounded; step function $f(x) = \lfloor x \rfloor$, greatest integer ≤ x, constant on intervals [n, n+1), jumps at integers, its graph is a staircase shape; absolute value f(x) = |x|, V-shaped graph, slope changes at 0.

Functions can be expressed in multiple forms, each useful in different contexts: verbal description, table of values (list of pairs), algebraic formula, graph, piecewise definition, recursive definition, parametric or integral form, and series representation.

Evaluating a function means finding or computing the output value f(x) for a given input value x. f(x) = $x^2-2x +4, f(2) = 2^2 -2\cdot 2 + 4 = 4 - 4 + 4 = 4, f(0) = 0^2 -2\cdot 0 + 4 = 4, f(1) = 1^2 -2\cdot 1 + 4 = 1 -2 +4 = 3$

The x-intercept is any point on the graph that intersects or crosses the x-axis. In other words, it is the value of x when the function (y-coordinate or y-value) is zero. The y-intercept is the point where the graph intersects or crosses the y-axis. y-coordinate of the point whose x-coordinate is 0, e.g., 2x - 3y = 6. x-intercept: set y = 0 → 2x = 6 ⇒ x=3, so (3, 0). y-intercept: set x = 0 → −3y = 6 ⇒ y = −2, so (0, −2).

f is said to have a local or relative maximum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≥ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$. f is said to have a local or relative minimum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≤ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$.💡Local extrema can only occur where the function stops rising or falling —either because the derivative is zero, the derivative doesn't exist, or you're at the edge of the domain.

First Derivative Test. Let f be differentiable on an open interval containing c, except possibly at c itself, and let c be a critical point (so f′(c) = 0 or f′ is undefined). Then:

Assume $\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = L$ and $\lim_{x \to \infty} = M$ exist as finite real numbers. Then:

Example: $\lim_{x \to \infty} 4 + \frac{3}{\sqrt{x}} = \lim_{x \to \infty} 4 + \lim_{x \to \infty}\frac{3}{x^{\frac{1}{2}}} = 4 + 0 = 4.$ $\lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{1}{x^{-2}} = \lim_{x \to -\infty} x^2 = \infty, \lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{1}{x^{2}} = 0$

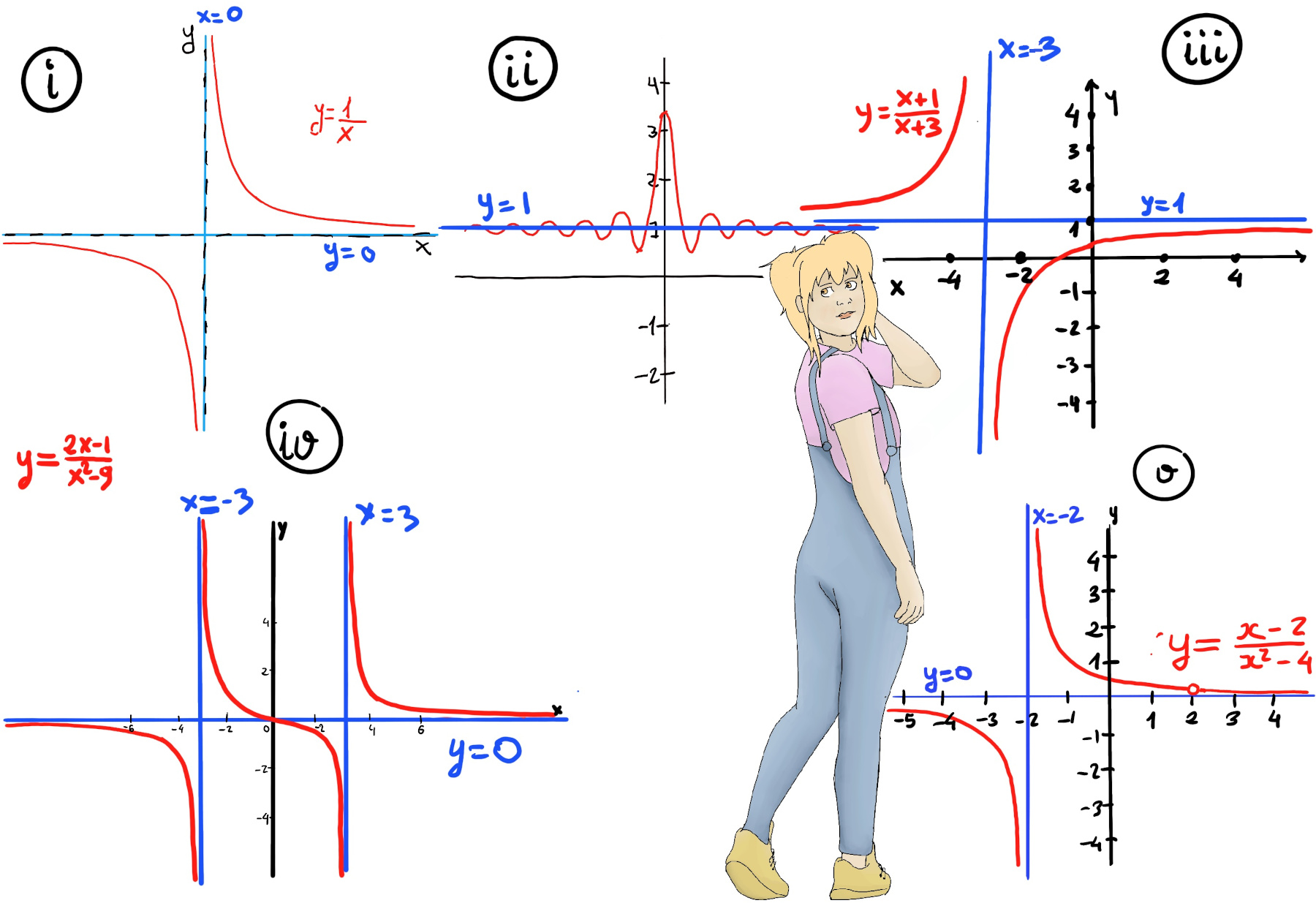

An asymptote is an horizontal, vertical, or slanted line such that the distance between the graph and the line approaches zero as the independent variable tends to infinity (or to a finite singular point). In other words, it is a line L that the graph approaches (it gets closer and closer, but never quite reach) as it heads or goes to positive or negative infinity or to some finite x-value.

Vertical asymptotes are vertical lines (perpendicular to the x-axis) of the form x = a (where a is a constant) near which the function grows without bound when x approaches a from at least one side. The line x = a is a vertical asymptote of f if at least one of the one-sided limits is infinite: $\lim_{x \to a^{-}}f(x)=\pm\infty$ or $\lim_{x \to a^{+}}f(x)=\pm\infty$, e.g., x = -2 is a vertical asymptote of $\frac{x+1}{x+2}, \lim_{x \to -2^{+}}\frac{x+1}{x+2} = \frac{-1}{0⁻} = \infty, \lim_{x \to -2^{-}}\frac{x+1}{x+2} = \frac{-1}{0⁺} = -\infty. y = \frac{1}{x}$ has vertical asymptote x = 0 (the y-axis), $\lim_{x \to 0^{+}}\frac{1}{x} = +\infin, \lim_{x \to 0^{-}}\frac{1}{x} = -\infin$.

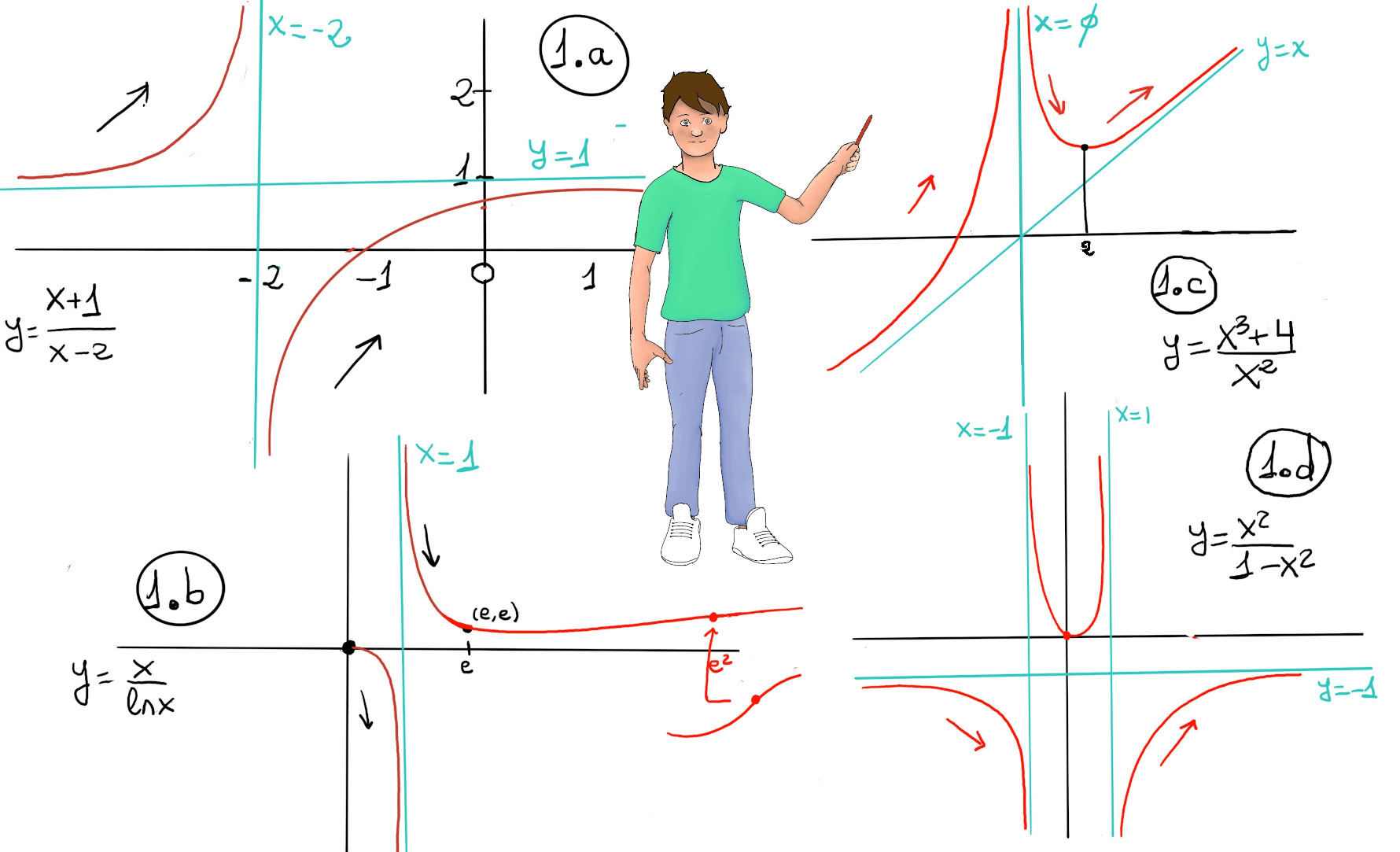

Often vertical asymptotes arise from zeros of the denominator in a rational function $f(x) = \frac{P(x)}{Q(x)}$ provided the zero of Q is not canceled by a common factor in P. If a factor cancels, we may have a removable singularity (a hole), not a vertical asymptote. The left and right behavior can differ. Example: $f(x)=\frac{x^2+x-2}{x+2}=x+2, \forall x \ne 1$, but the function as originally defined has a hole at x = 1. This is not a vertical asymptote — instead x = 1 is a removable discontinuity.

Horizontal asymptotes are a means of describing end behavior of functions and very closely related to limits at infinity. Horizontal asymptotes are horizontal lines (y = c, parallel to the x-axis) that the graph of the function approaches as x grows very large (positively or negatively). In other words, the function values get arbitrarily close to c as long as x is sufficiently large or more formally: $\lim_{x \to \infty}f(x)=c$ and/or $\lim_{x \to -\infty}f(x)=c$, e.g., y = 1 is a horizontal asymptote of $\frac{x+1}{x+2}$ because $\lim_{x \to \pm\infty}\frac{x+1}{x+2} = 1.$ $y = \frac{1}{x}$ has horizontal asymptote y = 0, $\lim_{x \to \pm\infty}\frac{1}{x} = 0$.

Different horizontal asymptotes on left and right: $f(x) = \frac{|x|}{x} + \frac{1}{x} = \begin{cases} 1 + \frac{1}{x} & x>0 \\ -1 + \frac{1}{x} & x<0 \end{cases}$. $f(x) \to y = 1 \text{ as } x \to +∞, f(x) \to y = -1 \text{ as } x \to -∞$. In other words, f has two different horizontal asymptotes.

Definition (linear/polynomial asymptote). A line y = m+b is an oblique (slant) asymptote as $x \to \infty$ if $\lim_{x\to\infty} [f(x) - (mx+b)] = 0.$ This means that the curve of f(x) gets more and more closer to the line y = mx + b as x grows large.

For an asymptote y = mx + b as $x \to \infty, m = \lim_{x\to\infty} \frac{f(x)}{x}, b = \lim_{x\to\infty} \bigl(f(x) - m x\bigr)$, provided both limits exist. The slope (m) may differ for $x \to+\infty$ and $x\to-\infty$; you should compute each limit separately, since the asymptote can differ on each side. Example: $f(x)=\dfrac{x^2+1}{x}, m=\lim_{x\to\infty}\frac{f(x)}{x}=\lim_{x\to\infty}\frac{x^2+1}{x^2}=1, b=\lim_{x\to\infty}\bigl(f(x)-x\bigr)=\lim_{x\to\infty}\frac{1}{x}=0$. Therefore, y = x is an oblique asymptote.

Definition. A polynomial is a function of the form f(x) = anxn + an-1xn−1 + ... + a2x2 + a1x + a0 where $a_n, a_{n-1},\cdots, a_0$ are real coefficients and n is a non-negative integer. The degree of a polynomial is the highest power of x with a non-zero coefficient. The domain is ℝ (polynomials are defined everywhere) and they are continuous and smooth (infinite differentiable) everywhere.

The end behavior of a polynomial is determined exclusively by the degree and leading coefficient.

Definition. Rational functions are ratios of two polynomial functions, f(x) = $\frac{p(x)}{q(x)} = \frac{a_nx^n+a_{n−1}x^{n−1}+…+a_1x+a_0}{b_mx^m+b_{m−1}x^{m−1}+…+b_1x+b_0}$ where an ≠ 0 and bm ≠ 0 (leading coefficients are non-zero). Domain: All real numbers except when q(x) = 0, e.g., $\frac{3-2x}{x-2}, \frac{x^3 + x^2 - 2x + 12}{x+3}.$

The end behavior of rational functions, say f(x) = $\frac{p(x)}{q(x)} = \frac{a_nx^n+a_{n−1}x^{n−1}+…+a_1x+a_0}{b_mx^m+b_{m−1}x^{m−1}+…+b_1x+b_0}$, depends entirely on the relationship between the degrees of numerator (n) and denominator (m). There are three distinct cases:

The sign of the limit depends on the sign of the ratio $\frac{a_n}{b_m}$ and whether n - m is odd or even (odd degree difference flips sign between +∞ and −∞).

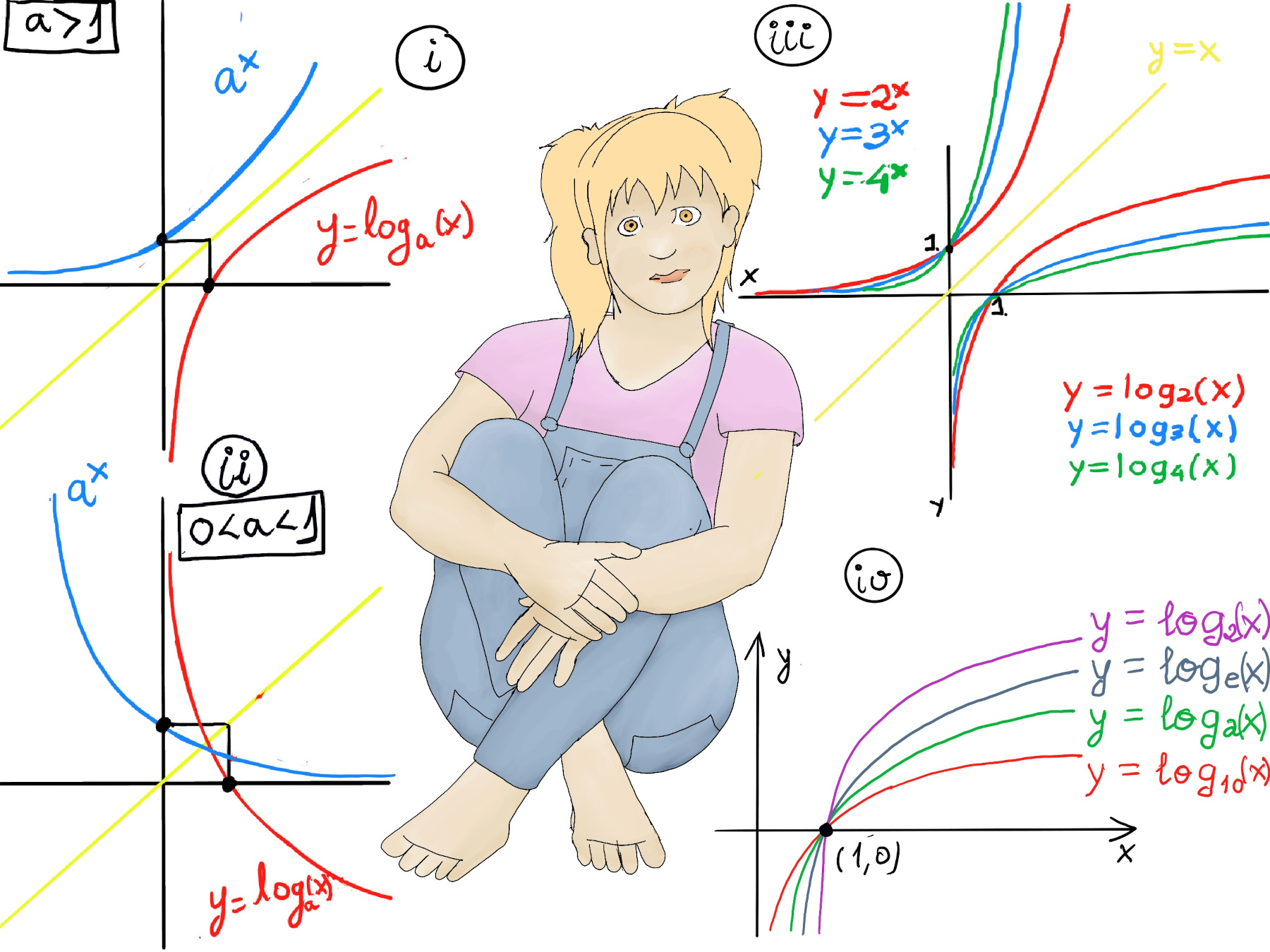

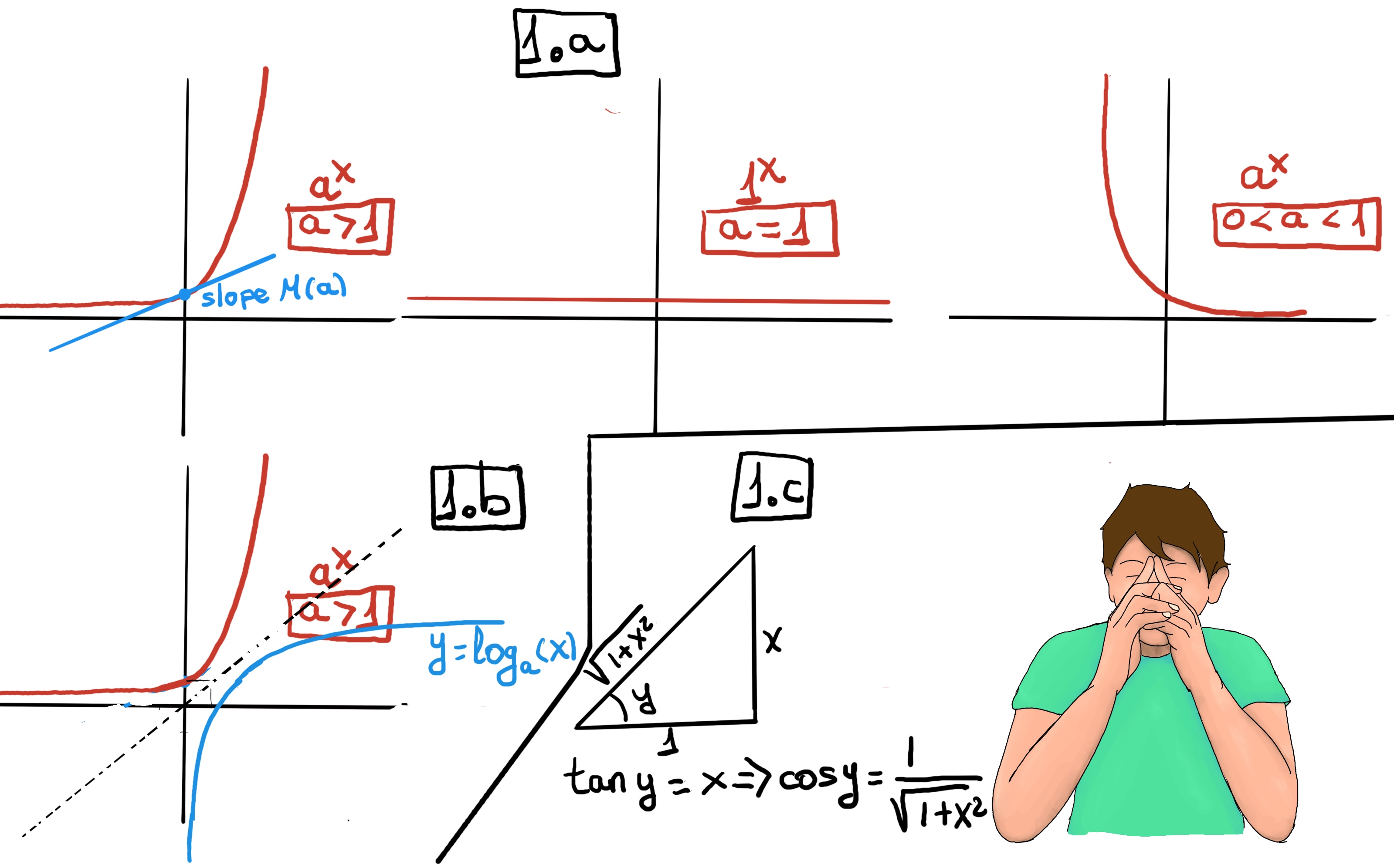

An exponential function is a mathematical function of the form f(x) = b·ax, where the independent variable appears in the exponent, and a and b are constants. The base a must be a positive real number (a > 0), and typically b > 0 as well..

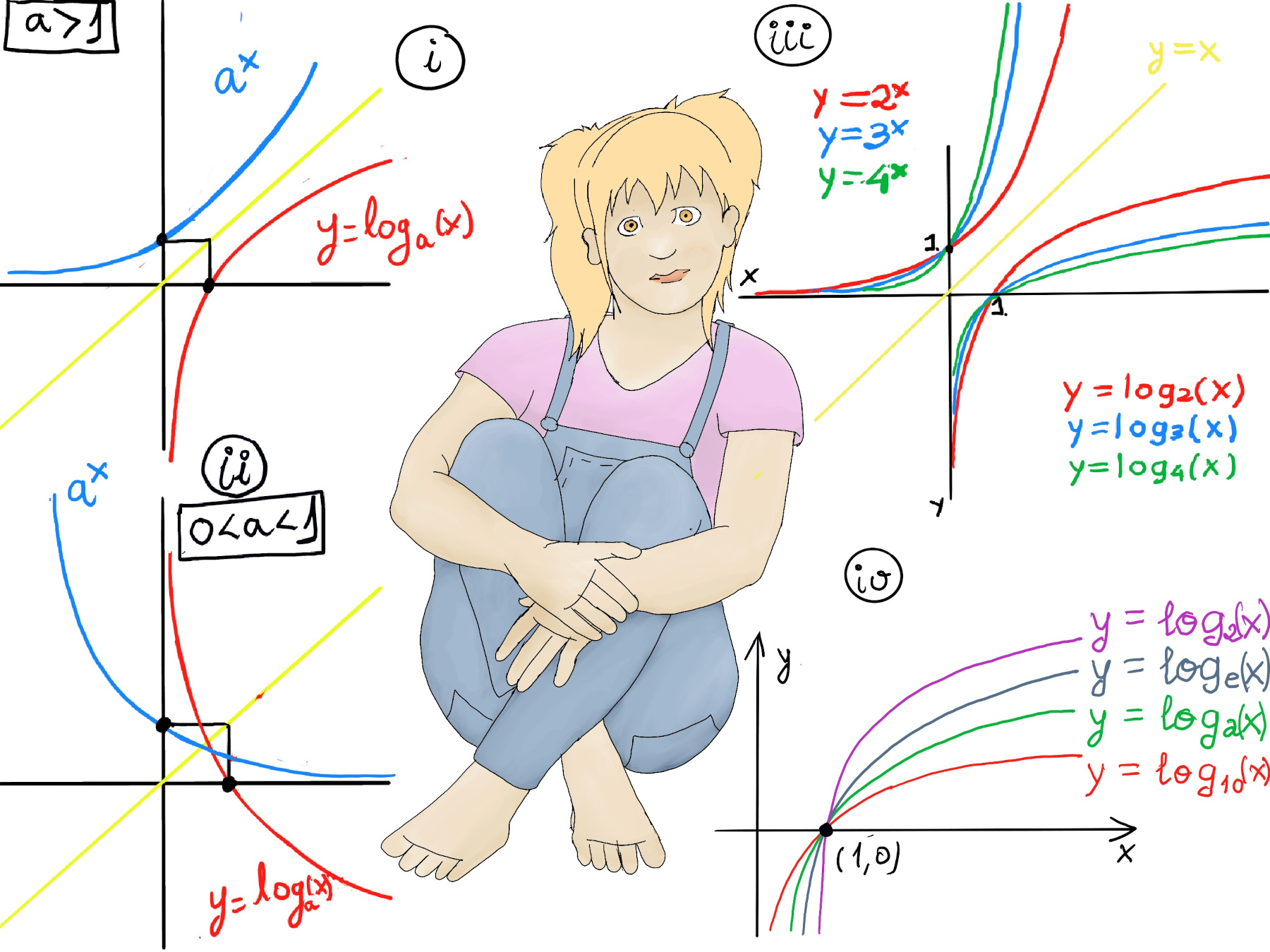

It is important to realize that as x approaches negative infinity, values become arbitrarily small but never actually reach zero, e.g., 2-5 ≈ 0.03125, 2-15 ≈ 0.00003052. Besides, the base of an exponential function determines the rate of growth or decay. For a > 1, the larger the base, the faster the function grows (Figure iii).

In mathematics, the logarithm is the inverse function to exponentiation. We call the inverse of ax the logarithmic function with base a, that is, logax=y ↔ ay=x. This means that the logarithm of a number x to the base a is the exponent to which a must be raised to produce x, e.g., log4(64) = 3 ↭ 43 = 64, log2(16) = 4 ↭ 24 = 16, log8(512) = 3 ↭ 83 = 512, but log2(-3) is undefined (logarithms of negative numbers don’t exist in the real number system).

As the inverse of exponential functions, logarithmic functions have the following characteristics:

The larger the base, the more slowly the logarithm grows. Equivalently, larger bases cause the graph to approach the vertical asymptote x = 0 more quickly. (Figure iii and iv).

A line y = L is a horizontal asymptote of f(x) if $\lim_{x \to +∞} f(x) = L$ and/or $\lim_{x \to -∞} f(x) = L$. In our particular case, L = 1, $\lim_{x \to +∞} f(x) = 1$ and $\lim_{x \to -∞} f(x) = 1$. Even though the function oscillates around y = 1 infinitely often for finite x, it eventually settles toward y = 1 as |x| becomes very large, e.g., $f(x) = 1 + \frac{sin(x)}{x}, g(x) = 1 + \frac{sin(x)}{x^2}$. The amplitude of oscillations decreases as |x| increases. For very large |x|, the function stays arbitrarily close to y = 1. Yet at many finite x-values, it crosses above and below y = 1.