|

|

|

“Beauty is so many things… and you are in all of them,” I said. “Wow! I thought that you were as romantic as a brick to the head or a nuclear bomb’s guts”, Susanne replied, Apocalypse, Anawim, #justothepoint.

“When bias narratives, misleading news without context, and blatant lies spread like wildfire, history needs to be rewritten and truth needs to be cancelled”, Anawim, #justothepoint.

Definition. A function f is a rule, relationship, or correspondence that assigns to each element x in a set D, x ∈ D (called the domain) exactly one element y in a set E, y ∈ E (called the codomain or range).

The pair (x, y) is denoted as y = f(x) where: x is the independent variable (input) and y is the dependent variable (output). Often, both the domain D and codomain E are the set of real numbers ℝ or subsets of ℝ. A mathematical function can be thought of as a black box (or machine) that takes an input from its domain and produces exactly one output in its codomain. Inside the machine lives a specific rule (formula, procedure, or mapping) that dictates or tells you which output corresponds to each input, and a key property is uniqueness —each input maps to a single, deterministic output. No input can ever produce two different results (Figure E). The function f(x) = x2 accepts any real number x (domain: ℝ) and returns exactly one non-negative value x2 (output in codomain: [0,∞)). The input 3 always yields 9, never any other value.

D is the domain, the set of all possible inputs. E is the codomain or range, the set of all possible outputs.

Key property💡: Each input has exactly one output. (No input is assigned two different outputs — this is the vertical line test!)

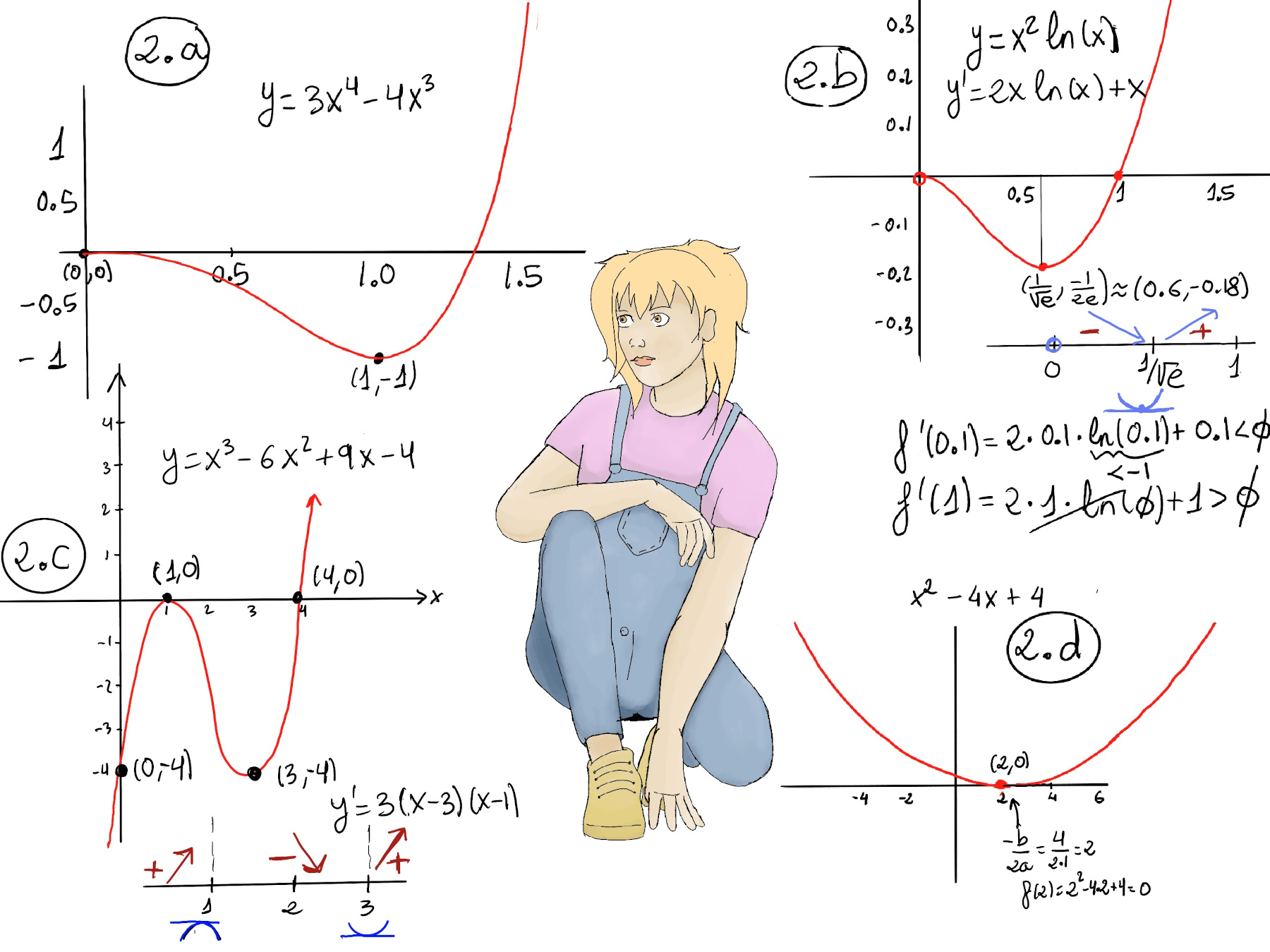

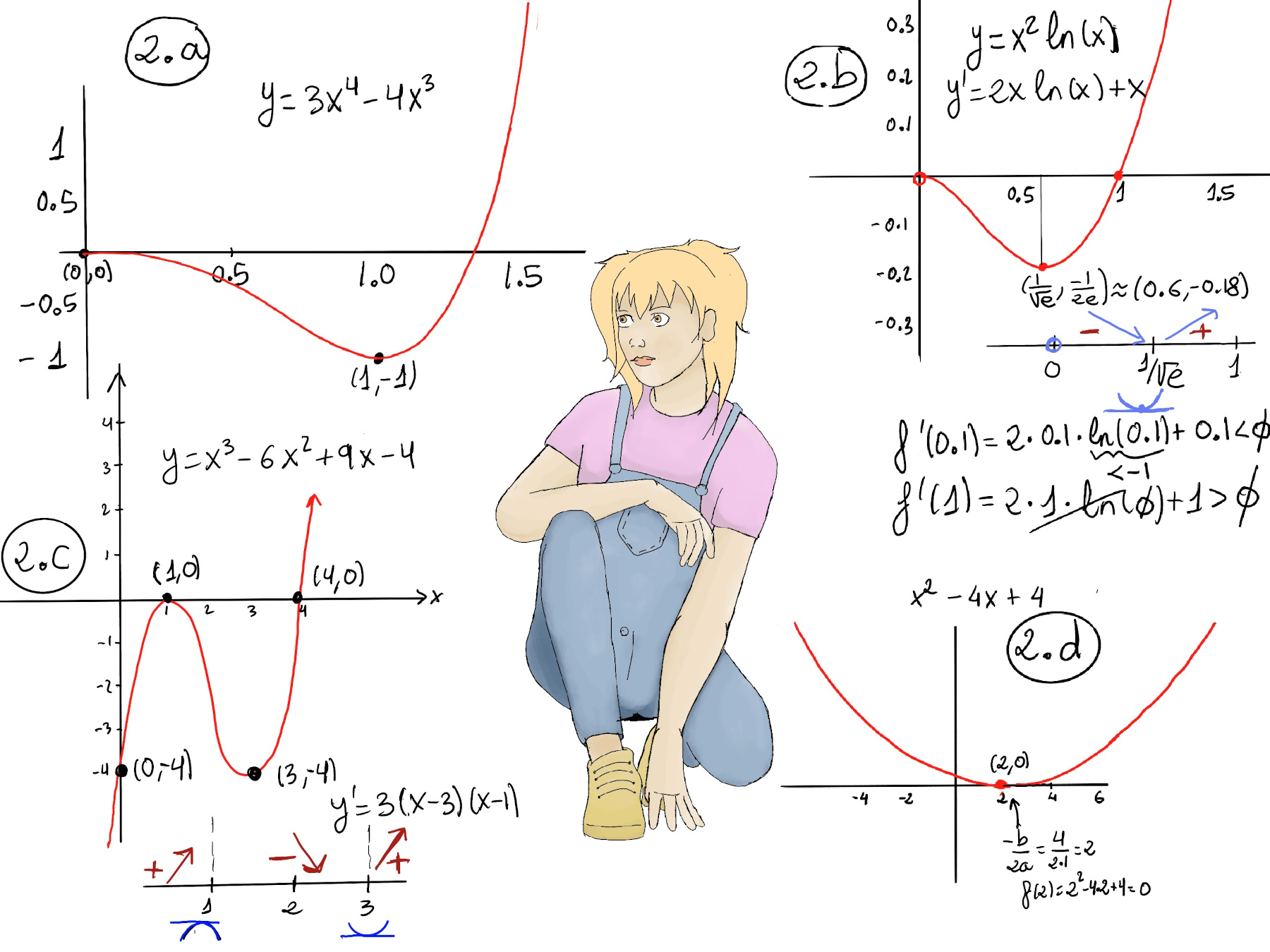

Examples: constant, f(x) = c, horizontal line, slope = 0; linear, f(x) = mx + b, straight line, constant slope m and y-intercept b; quadratic $f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c$, u-shaped or inverted U, opens up (a > 0) or down (a < 0), vertex at x = $\frac{-b}{2a}$, symmetry about vertical axis through vertex; polynomial, $f(x) = a_n x^n + \dots + a_0$, a smooth and continuous curve, n roots (counting multiplicity), end behaviour determined by its leading term $a_n x^n$; exponential function, $f(x) = a \cdot b^x, a \ne 0, b \gt 0$, rapid growth (b > 1) or decay (0 < b < 1); trigonometric functions, $\sin(x), \cos(x), \tan (z)$ oscillatory, periodic behavior (period 2π for sin/cos, π for tan), sin and cos are bounded between -1 and 1, but tan is unbounded; step function $f(x) = \lfloor x \rfloor$, greatest integer ≤ x, constant on intervals [n, n+1), jumps at integers, its graph is a staircase shape; absolute value f(x) = |x|, V-shaped graph, slope changes at 0.

Functions can be expressed in multiple forms, each useful in different contexts: verbal description, table of values (list of pairs), algebraic formula, graph, piecewise definition, recursive definition, parametric or integral form, and series representation.

Evaluating a function means finding or computing the output value f(x) for a given input value x. f(x) = $x^2-2x +4, f(2) = 2^2 -2\cdot 2 + 4 = 4 - 4 + 4 = 4, f(0) = 0^2 -2\cdot 0 + 4 = 4, f(1) = 1^2 -2\cdot 1 + 4 = 1 -2 +4 = 3$

The x-intercept is any point on the graph that intersects or crosses the x-axis. In other words, it is the value of x when the function (y-coordinate or y-value) is zero. The y-intercept is the point where the graph intersects or crosses the y-axis. y-coordinate of the point whose x-coordinate is 0, e.g., 2x - 3y = 6. x-intercept: set y = 0 → 2x = 6 ⇒ x=3, so (3, 0). y-intercept: set x = 0 → −3y = 6 ⇒ y = −2, so (0, −2).

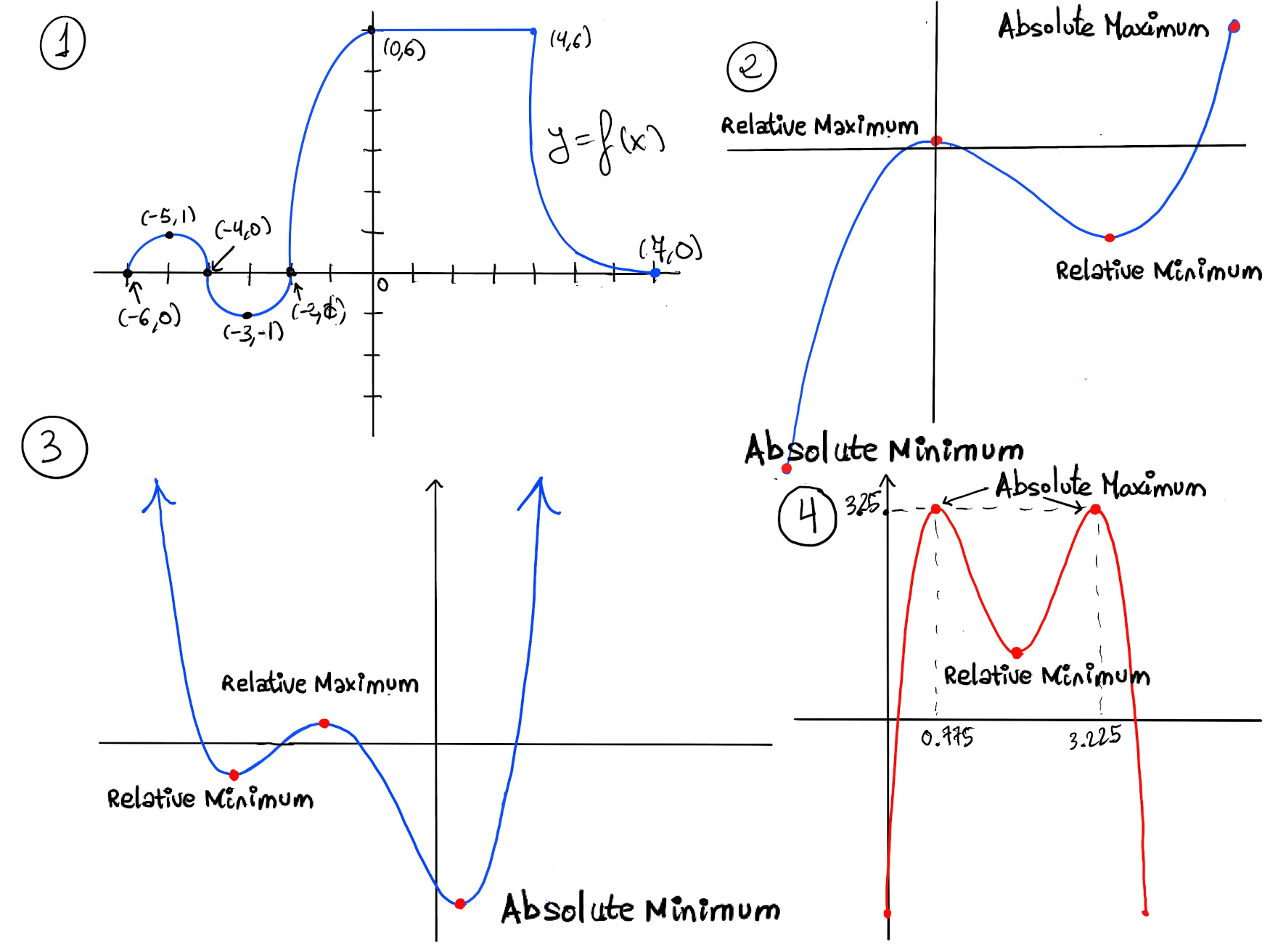

f is said to have a local or relative maximum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≥ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$. f is said to have a local or relative minimum at c if there exists an interval (a, b) containing c ($c \in (a, b)$) such that f(c) ≤ f(x) $∀ x \in (a, b) ∩ D$.💡Local extrema can only occur where the function stops rising or falling —either because the derivative is zero, the derivative doesn't exist, or you're at the edge of the domain.

First Derivative Test. Let f be differentiable on an open interval containing c, except possibly at c itself, and let c be a critical point (so f′(c) = 0 or f′ is undefined). Then:

In calculus, we are often interested in identifying the largest and smallest values that a function can attain. These values are called the extrema (plural of extremum).

The maxima and minima (the respective plurals of maximum and minimum) of a function are the largest and smallest values of the function, either within a given range (or a specific neighborhood) (the local extrema, i.e., local or relative maximum and minimum) or on the entire domain (the global extrema, i.e., the global or absolute maximum and minimum). Intuitively, local extrema can be visualized as hills and valleys on a graph, while absolute extrema represent the highest peak and the deepest valley of the function.

Let f be a real-valued function defined on a domain D. The function f has an global or absolute maximum at x = c ∈ D if f(c) ≥ f(x) ∀ x ∈ D. Similarly, the function f has a global or absolute minimum point at x = c ∈ D if f(c) ≤ f(x) ∀ x ∈ D.

The absolute maximum or minimum value is f(c), and the points (c, f(c)) are called the absolute extreme points.

A function does not necessarily have absolute extrema. For example, a line with positive slope extends infinitely in both directions.

Figure 3 illustrates a function that does not have an absolute maximum. Besides, a graph can only have one absolute minimum or maximum, but multiples x-values could obtain them as it is illustrated on figure 4. The function has an absolute maximum value of y = 3.25 which is obtained both at x = 0.775 and 3.225.

One of the most important theoretical results concerning absolute extrema is the Extreme Value Theorem.

Extreme Value Theorem / Weierstrass Theorem Let $f : [a, b] \to \mathbb{R}$ be a continuous function, where [a, b] is a closed, bounded interval in $\mathbb{R}$. Then there exist points $c, d \in [a, b]$ such that $f(c) = \sup \{ f(x) : x \in [a, b] \}, f(d) = \inf \{ f(x) : x \in [a, b] \}.$ In other words, f attains both its maximum and minimum values on ( [a, b].

Proof:

Recall. Bolzano–Weierstrass Theorem. Every bounded sequence of real numbers has a convergent subsequence whose limit lies in the closure of the set.

Step 1. The Boundedness Theorem: If $f : [a, b] \to \mathbb{R}$ is continuous, then f is bounded on [a, b], that is, there exist real numbers m, M such that for all $x \in [a, b]. m \leq f(x) \leq M$.

Suppose, for contradiction, that f is not bounded above. Then, $\forall n \in \mathbb{N}, \exist \text{ (there exists) } x_n \in [a, b]$ such that $f(x_n) > n$.

The sequence {$x_n$} is contained in the compact (closed and bounded) interval [a, b], so by the Bolzano–Weierstrass Theorem, there exists a convergent subsequence {$x_{n_k}$} with limit $x^* \in [a, b]$ (Note: $x^* \in [a, b]$ because [a, b] is closed).

By continuity, $f(x_{n_k}) \to f(x^*)$, but by construction $f(x_{n_k}) > n_k \to \infty \implies f(x^*) = +\infty$, which contradicts that $f(x^*)$ is a real number. Thus, f is bounded above. A similar argument shows f is bounded below.

Step 2. Existence of Supremum and Infimum. Let S = {f(x) : $x \in [a, b]$}. By Step 1, S is bounded. By the completeness of $\mathbb{R}$, S has a supremum M and an infimum m.

The Completeness Axiom of the Real Numbers states that every non-empty set of real numbers that has an upper bound must also have a least upper bound (supremum) within the set of real numbers.

Step 3. The attainment of bounds: By the properties of continuous functions on closed intervals, these bounds M and m are actually achieved by f at specific points c and d within the interval.

Proof.

We now show that there exists $c \in [a, b]$ such that f(c) = M.

Suppose, for contradiction, that f(x) < M for all $x \in [a, b]$. Define the auxiliary function $g(x) = \frac{1}{M - f(x)}, \forall x \in [a, b]$.

Since $f(x) < M, M - f(x) > 0$, so g(x) > 0 for all x (we only need non-vanishing denominators). The function g is continuous on [a, b] (as the composition of continuous functions and $M - f(x) \ne 0$), and thus, by the Boundedness Theorem, is bounded above: there exists K > 0 such that $g(x) \leq K$ for all $x \in [a, b]$. Therefore, $M - f(x) \geq \frac{1}{K} \implies f(x) \leq M - \frac{1}{K}$ for all $x \in [a, b]$. But $M - \frac{1}{K} < M$, contradicting the definition of M as the least upper bound. Therefore, there must exist $c \in [a, b]$ such that f(c) = M.

The proof for the minimum is analogous: either apply the above argument to -f, or repeat the steps with $m = \inf S$.

To find absolute extrema or the extrema of a continuous function f on a closed interval [a, b], one needs to consider critical points and endpoints of the domain, and use the following steps.

Additional information. x-intercept: (4, 0) and (1, 0). y-intercept (0, -4) and there’s no asymptotes.

If a < 0, the parabola opens downward and the vertex is an absolute maximum, e.g., -x2+x-6 has an absolute maximum at $(\frac{-b}{2a}, f(\frac{-b}{2a})) = (0.5, -5.75)$ because a = -1 < 0.

Why It Works? $f'(x)=2ax + b, f'(x) = 0 \iff x = \frac{-b}{2a}$

f’’(x) = 2a. If a > 0, 2a > 0 $\implies x = \frac{-b}{2a}$ is a local minimum. If a < 0, 2a < 0 $\implies x = \frac{-b}{2a}$ is a local maximum.